Results of the top-down research approach

Policy blockers and enablers relevant for the consolidation and scaling up of FASS Food supply chains in the EU

Through a series of international workshops gathering representatives from civil society organizations, EU policy makers (European Commission and European Parliament), EU institutions (EESC), as well as EU farmers’ representatives, and facilitating the exchange of learnings and good practices, FASS-Food has mapped policy blockers and enablers at the EU level, including the role of legislation, soft law and labels.

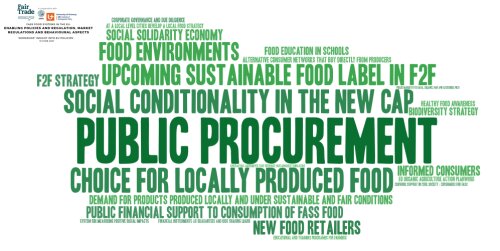

The frequency map shown below displays the key enablers promoting FASS Food supply chains in the EU, from a regulatory, market, and behavioural point of view. Enablers presented in this image are the result of the discussion that took place during FASS-Food workshops. Concepts in larger size are those most agreed with by participants.

The frequency map shown below displays the key blockers hampering FASS Food supply chains in the EU, from a regulatory, market, and behavioural point of view. Blockers presented in this image are the result of the discussion that took place during FASS-Food workshops. Concepts in larger size are those most agreed with by participants.

A smart mix of policy recommendations to promote FASS-Food chains in the EU

This document reflects the outcome of the different ‘top-down’ moments that were organized in the course of the project. The implementation of the Farm to Fork Strategy and the framework of the Sustainable Food Systems Law acted as lighthouses of the project, but these frameworks were enriched with reflections on connected and interdependent policy areas.

A smart mix of recommendations means different actions that different actors need to execute so that FASS Food supply chains in the EU are ensured. Those actions do not only target EU policymakers, nor only EU legislation or policies, since the project believes that there is a shared responsibility in achieving sustainable food supply chains in the EU. These recommendations were designed on the basis of the identified current blockers and enablers in EU policies that, respectively, impede or promote scale up of FASS Food supply chains in the EU, as well as on the identified EU policies windows of opportunity in the short, medium, and long term.

1. Public procurement – Sustainable food public procurement could directly contribute to making sustainable products the default and accessible choice for EU consumers. Minimum mandatory criteria also related to social sustainability aspects (socially responsible public procurement), would make contribute to offering EU consumers with fair food products (extracted, harvested or produced in fair and decent conditions, respecting labour standards and covering a minimum price for production of sustainable products, as central elements).

2. Social solidarity economy – Promotion of social economy may directly lead to promotion of social enterprises and alternative business models, such as the FASS Food pilots. Thus, tackling blockers such as current business and market models locking farmers in unsustainable farming practices; and the lack of acknowledgement and support to sustainable business and farming models that contribute to achievement of social economy.

3. The EU action plan for organic production – Although this is general an enabler for FASS Food supply chains in the EU, certain shortcomings shall be addressed in order to reach the target of 25% land used for organic farming by 2030. This refers, mainly to, insufficient ambition and budget to incentivise farmers to convert to organic farming. As well as to the lack of environmental ambition of the eco-schemes included in the new CAP, and the problems for farmers to combine organic schemes with eco-schemes.

4. Products made with forced labour – Work conditions; lack of transparency in supply chains, insufficient integration of F2F and Social Solidarity Economy; migration conditions and EU migration rules; lack of coherence between food policy and socio-economic policy; are part of the blockers identified and that could be directly or indirectly addressed though the prohibition to place products made with forced labour in EU market. Consequently, contributing to an enabling environment for products to be made in fair conditions and in respect of Human Rights, and thus, contributing to achievement of social sustainability in EU food systems.

5. EU competition policy – Focused too narrowly on ensuring low prices and short-term economic benefits to end-consumers in Europe, EU competition policy makes it difficult to implement multistakeholder sustainability agreements, especially those involving competitor cooperation. This approach goes counter to the EU Treaties and the European Green Deal, which foresee that all EU policies should contribute to achieving a sustainable future. A revision of Horizontal Guidelines, to address the need for legal certainty by including a chapter on sustainability agreements in the Guidelines on Horizontal Cooperation Agreements, would facilitate and encourage sectorial conversations involving competitors, while making clear that sustainability cannot be invoked as a smokescreen for anti-competitive behaviour. In parallel, the European Commission is working on guidelines on antitrust derogations in sustainability agreements in agriculture, in context of the Common Market Organization.

6. A legislative framework for sustainable food systems (F2F Strategy) – This initiative from the F2F strategy has been identified as the main enabler for FASS Food supply chains in the EU. A well-designed framework could address most of the identified blockers as it will most likely establish a combination of obligations and responsibilities for all (or most) actors involved in the EU food system (including Member States). This legislative framework should, inter alia, promote community supported agriculture and other forms of local solidarity partnerships between producers and consumers, make sustainable products the default and accessible choice for consumers, and regulate market pressures.

7. Regulation on the sustainable use of plant protection products – The European Commission adopted a proposal for new regulation on the sustainable use of plant protection products, including targets to reduce by 50% the use and risk of chemical pesticides by 2030. This regulation could tackle FASS-Food blockers particularly linked to environmental sustainability of food products.

8. EU regulation for deforestation-free supply chains – End 2021, the European Commission presented its proposal for a regulation on deforestation-free products. The proposed new rules imply that at least six food and agricultural commodities (cocoa, coffee, beef, soya, palm oil and wood) and some derived products must not be linked to deforestation when they are being either exported from or imported to the EU. The Regulation may represent a leverage for FASS-chains in the EU and abroad, but only if well shaped. Several points have to be addressed, such as the importance of recognising the role and responsibilities of each of supply chains actors, the need to adopt a broad notion of forest degradation, the extension of the scope beyond forest into different habitats, and so on.

9. Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) – The European Commission has introduced its proposal for Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (CSDDD). Its aim is to foster sustainable and responsible corporate behaviour and to anchor human rights and environmental considerations in companies’ operations and corporate governance.

10. Sustainable food labelling proposal (F2F strategy) – The F2F’s proposal for a sustainable food labelling framework would empower consumers to make sustainable food choices. This initiative should be introduced in 2024 and it is being developed alongside the proposal for a legislative framework for sustainable food systems (2023), and the minimum mandatory criteria for sustainable food procurement to promote healthy and sustainable diets in schools and public institutions (initially announced for 2021).

11. Evaluation of UTP Directive 2019/633 – The Directive 2019/633 on unfair trading practices in business-to-business relationships in the agricultural and food supply chain aims at strengthening the position of farmers in the supply chain and addressing abuse of power in trading relationships. The Directive entered into force at Member State level in 2021 and should be evaluated by the Commission in 2025. The evaluation of the Directive is identified as an enabler for FASS Food supply chains in the EU, as it could address current shortcoming of the Directive and/or to include good practices introduced by Member States that directly address low prices paid for agri-food products and contribute to rebalance power in agricultural trading relationships.

12. New Common Agricultural Policy (CAP 2027) – The lack of social dimension in the Common Agricultural Policy was one of the biggest identified blockers for enabling FASS Food supply chains in the EU. Though it has been incorporated in current CAP, there is still space for improvement in that and other aspects of the CAP. The new CAP allegedly paves the way for a fairer, greener and more performance-based CAP; by seeking to ensure a sustainable future for European farmers, provide more targeted support to smaller farms, and allow greater flexibility for EU countries to adapt measures to local conditions. Nonetheless, it has been criticized for not introducing necessary reforms to adequately address climate change, loss of biodiversity, and the lack of fairness in the distribution of subsidies. Social conditionality should further develop so it unravels its potential to act as an enablerfor FASS-Food supply chains in the EU.

These recommendations, rather than micro-interventions, aim to reflect institutional and organizational changes that can support and facilitate the development of short and collaborative food systems in the EU. The identification of multiple intervention spaces and the systemic execution of these actions may have a positive impact on the development and consolidation of FASS Food supply chains in the EU.

Read the complete top-down Recommendations to promote FASS-Food supply chains in the EU here.

Results of the bottom-up research approach

3 case study reports on different FASS-Food systems in Belgium, Italy and Greece

The research team engaged with three concrete cases of alternative food networks that aim at linking small scale farmers and SMEs to consumers in a sustainable and economically fair way. We used WFTO-Europe network to pick three pilots in three different EU countries and markets:

- Kort’om Leuven – a farmers’ logistic cooperative constituted in Leuven (Belgium) in 2020.

- Solidale Italiano – a workers’ cooperative shop constituted in Athens (Greece) in 2011.

- Syn Allois – a partnership between a farmers’ cooperatives and a Fair Trade organization launched in Italy in 2010.

A policy brief for the consolidation and scaling up of FASS-Food chains in the EU

This document summarizes the main questions and findings of the research project: the obstacles that the different actors are facing, the points of leverage that they identified, the strategies that they deployed – or envisage to deploy – to develop FASS food chains, and 4 policy recommendations at the local and EU level.

The research identified 3 strategies based on the case studies: the creation of 1) farmers’ cooperatives mutualizing logistics and facilitating economies of scales, 2) distinctive labels through which Fair Trade intermediaries integrate and empower sustainable farmers, and 3) alternative ecosystems where small farmers and consumers focused on shared sustainability values support each other.

As well, 5 key behavioral and policy blockers for FASS chains were identified at the bottom-up level: 1) the imposition of mainstream retailers’ unilateral standards and requirements, 2) a lack of awareness about the impact of food choices on sustainability on consumers’ side, 3) the limited affordability diverting vulnerable segments of the population from buying sustainable food, 4) the difficult access to conventional financial instruments to initiatives pursuing sustainability goals, 5) the narrow focus on cheap food adopted by the current legal framework of as a measure of “consumer’s welfare”.

The findings led to the elaboration of 4 policy recommendations at the EU and local level:

1. Using socially and ecologically responsible public procurement – Public procurement particularly is a pivotal tool to make a positive shift in the policy framework from consumers’ individual consumption behaviour to a more collective and systemic dimension. Through socially and ecologically responsible public procurement, public authorities can support small-scale farming, create job opportunities and a market for local producers, guarantee decent work, favour social and professional inclusion, reduce their carbon footprint and make sure that an increasing number of citizens has access to healthy and nutritious food. Along with better purchasing practices, a reflection on the wealth distribution in society and the difficulties of a large part of the EU population to take the choice of sustainable and fairly remunerated producers is urgently needed.

2. Designing and implementing integrated urban food policy frameworks – These frameworks are designed to address multiple food systems challenges, and require multiple government departments and policy areas to be bridged and novel governance bodies to be established. Challenges and externalities of a wrong food system are an undeniable fact: the world trade has lengthened the distance between the producers and consumers, the impact of logistics on pollution and congested traffic, the waste of food still usable for human consumption. Integrated urban food policies encompass diverse but interconnected initiatives, such as financial support to local solidarity and social economy organizations to kick-off and consolidate FASS initiatives such as the pilots examined in this research project, the creation of public agencies that act to promote local food supply chains, for instance, through the creation of a big peri-urban productive surface delivering FASS food products to city inhabitants; and, last but not least, a socially-engaged university system producing knowledge to inform local policy-makers as well as to support activism of micro and macro associations of social actors.

3. Creating city-based food councils – Food councils are community-based coalitions, consisting of multiple organizations and individuals, that help promote more FASS food systems. These councils aim to build connections across stakeholders and collaborate to improve health, food access, natural resource protection, economic development, and production agriculture for all its community’s citizens. These can also provide business development support to local solidarity and social economy organizations to kick-off and consolidate FASS initiatives. Broadly speaking, these food councils ought to work in order to: (a) engage experts to better understand the food environment; (b) connect decision makers and stakeholders to align programs and initiatives; (c) inform and educate leaders, businesses and civil society; (d) recommend program and policy change to affect the local food system

4. Food welfare policies – A significant proportion of people living today find it difficult to get access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life. This is especially true for low-income and no-income segments of populations. Therefore, public spending programs that provide food-purchasing support to these population segments in order to get access to FASS food products is important to prevent these products from being available only to élites.