Insights from the Lecture by dr. Kholoud Al-Ajarma at USI (16.10.2025)

Authors: Lara Sarcinella -PhD student at the Department of History (Sohifin research project), University of Antwerp and Kim Overlaet-Research manager-Department of History, University of Antwerp

Dr Kholoud Al-Ajarma is a lecturer at the Alwaleed Centre for the Study of Islam in the Contemporary World at the University of Edinburgh (Department of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies). She is an award-winning Palestinian anthropologist, photographer, filmmaker and human rights activist, with research experience in the Middle East, North Africa and Latin America. Her research focuses on topics such as refugee rights, political ecology, religious experience and Palestinian diaspora communities. Until the end of December 2025, Al-Ajarma is a visiting scholar at the Urban Studies Institute of the University of Antwerp.

As part of this residency, Dr. Kholoud Al-Ajarma gave a guest lecture on October 16, 2025, about her work with and on various Palestinian refugee camps in the West Bank, and Lebanon. There, she is particularly committed to preserving and documenting the ecological knowledge and agriculture of the indigenous Palestinian population in the Israeli-occupied territories, and to developing educational programs for young people and women in Palestinian refugee camps. Deeply impressed by the lecture and the resilience and sumud (steadfastness) of the Palestinian refugees, we are pleased to highlight the work and research of Dr. Kholoud Al-Ajarma.

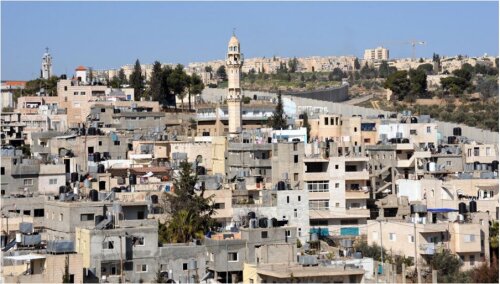

Aida (2025) © Kholoud Al-Ajarma

From seasonal agriculture to nurturing knowledge and agro-resistance

After the Nakba, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were brutally expelled from their villages. Most ended up in refugee camps in Gaza, the West Bank and neighbouring countries such as Syria, Lebanon and Jordan. In recent decades, refugee camps such as Aida (Bethlehem, West Bank) have grown into urban centres with enormous population densities (approximately 6,400 people per 0.071 km² in Aida). Ad hoc assembled and often unstable buildings three to four stories high are crammed together. Several generations often live together in a small flat, there is very little privacy and there is no comfort whatsoever. According to Dr Al-Ajarma, who grew up in Aida, these living conditions are exacerbated by discriminatory measures, illegal arrests, raids and destruction of land and property. As in other refugee camps, access to (running) water is strictly controlled. In a “good” month, the average family in Aida has running water for only two hours a week.

Before 1948, agriculture was the main source of income and livelihood for most Palestinians, and for those who were not expelled in 1948, this is still the case. However, the densely populated Palestinian refugee camps lack (green) open spaces, while the Israeli separation wall on the West Bank has denied the Palestinians in Aida access to (agricultural) land that was previously accessible to them since 2002.

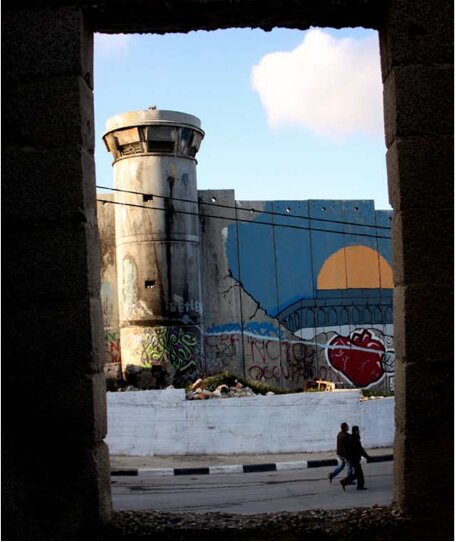

Aida wall (2025) © Kholoud Al-Ajarma

Some key concepts in Dr Kholoud Al-Ajarma's research are political ecology of displacement, ecological memory and agro-resistance. Initiatives such as Refutrees are peacefully engaging in “agro-resistance” against the forced urbanisation of the Palestinian agricultural lifestyle and dependence on food imports. By growing vegetables in the scarce green spaces in and around the refugee camps and constructing rooftop gardens for vegetable cultivation, they are promoting Palestinian food sovereignty. These small (rooftop) gardens are also important meeting places, where knowledge is transferred across generations.

In Aida, among other places, Dr. Al-Ajarma uses interviews to investigate the crucial role of older women in preserving and passing on Palestinian culture, history and knowledge to their children and grandchildren. They are the guardians of knowledge about working the land, the medicinal properties of herbs, and the management of (limited) water resources. Palestinian families cherish their roots and collective memories, which take shape and are passed on through the generation of their grandparents and parents, and are always interwoven with (intergenerational) trauma, grief and hope. In the memory of the older generations, the Palestinian relationship to the land was similar to that with a beloved family member, based on the principle: ‘If you take care of the land well, it gives to you.’ Dr Al-Ajarma's research highlights the crucial and layered meanings of small-scale agriculture for Palestinian refugees, as a memory, as resistance, as “home”-making.

Seeds of hope?

Millions of displaced Palestinian families, men, women, and children have been hoping for decades to return to their homes, villages, properties, and farmlands. That right of return was granted to them by the UN (December 1948) and was enshrined in international law and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Aida, Bethlehem, via https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palestinian_key#/media/File:Aida_Camp_entrance.jpeg consulted on 18/10/25

The Aida refugee camp, for example, is known worldwide for its monumental gate in the shape of a keyhole. Resting on the keyhole is an enormous key, symbolising the countless house keys that generations of Palestinian refugees have carefully preserved as a sign of hope and connection to their lost homes.

In anticipation of a possible return and revival of Palestinian agriculture, various organisations, such as the Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC), have established “seed banks”. These carefully preserve indigenous and traditional seeds – from grains and legumes to herbs and vegetables – with a view to the sustainable protection of biodiversity and future reintroduction, also taking climate change into account (e.g. Palestinian Heirloom Seed Library in Battir near Bethlehem). Like the rooftop and vegetable gardens, these seed banks are part of the broader pursuit of food sovereignty and serve as repositories of Palestinian knowledge and (agro)culture.

Israel has colonised Palestinian agricultural land on a large scale and uses access to and cultivation of that land as a political tool. According to Dr Al-Ajarma, Palestinians are prohibited from foraging certain crops, such as za'atar. In a context where access to food and water is strictly controlled, the small (vegetable) gardens and rooftop gardens in the refugee camps become places of peaceful resistance.

Representations of the (Palestinian) roots regularly appear in the streetscape of Aida (see photo). The peaceful forms of resistance and initiatives of the women studied by Dr Kholoud Al-Ajarma contribute to protecting and perpetuating Palestinian culture and identity, which are connected to the land.

Street art in Al-Azza2025 © Kholoud Al-Ajarma

More info about the research by dr. Kholoud Al-Ajarma, via: https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/en/persons/kholoud-al-ajarma/publications/