A bit of history

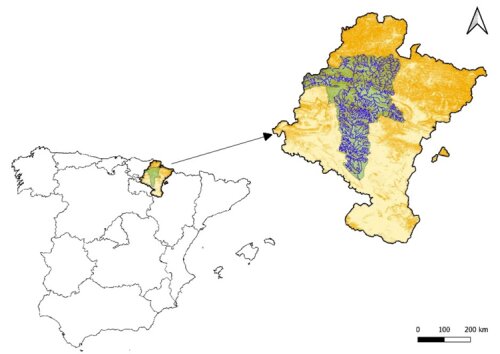

The Arga River, one of the main tributaries of the Ebro River in north-eastern Spain, drains a basin of 2733 km2, almost entirely within the Chartered Community of Navarre (96%), with a small fraction, (4%) extending into the neighbouring the Basque Country (Fig. 1) [1]. From its headwaters in the Western Pyrenees at nearly 1500 m a.s.l., the river flows across steep karstic terrain, where fractured rocks and dense forests favour infiltration and groundwater recharge. As it descends, the Arga connects contrasting geographical units: the ridges of the Pyrenees, the valley of the Basque-Cantabrian mountainous, and the plains of the Ebro depression. This pronounced north-south gradient shapes its climate, geology, hydrology and ecosystems. Finally, at just 276 m a.s.l., the river joins the Aragón River in a fertile floodplain that has been intensively transformed by human activity [1].

Figure 1. Chartered Community of Navarre’s location in Spain showing the Arga basin in green and the Arga River in blue.

Climate, geology and hydrology

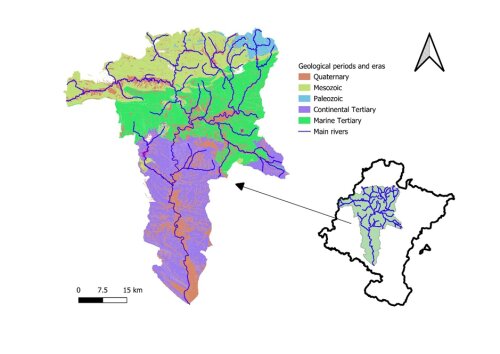

The Arga basin is marked by strong climatic contrast. In the north, under Atlantic influence, rainfall is abundant and evenly distributed through the year (1400-1600 mm year-1). Towards the Mediterranean south, precipitation decreased sharply to less than 350 mm per year [1]. Geology follows the same gradient. In the Pyrenees, fractured and folded Palaeozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic marine formations dominate and favour infiltration and aquifer recharge. Further south, Tertiary continental deposits of the Ebro depression create less permeability soils, where agriculture and reduced vegetation cover enhance surface runoff (Fig. 2). Hydrology mirrors these changes. In the headwaters, the Arga displays a pluvio-nival regime, combining rain and snowmelt, while downstream it evolves into a Mediterranean-type regime with more irregular flows. Discharge increases from 3 m3 s-1 in the upper parts to over 40 m3 s-1 before joining the Aragón River. Flood peaks usually occur at the end of winter and during spring, sometimes exceeding 60 m3 s-1 . Arga hydrology reflects its dual nature as both a surface and groundwater system. Its mean annual discharge is about 1,792 hm³, while significant subsurface resources are stored in the Andia and Aralar mountain ranges, as well as in an extensive alluvial aquifer in its lower course. This aquifer is recharged not only by rainfall but also by irrigation surpluses and floodwater retained along the riversides [1].

Figure 2. Geological map of the Arga basin indicating the origin of the different lithologies.

Society and the Arga River

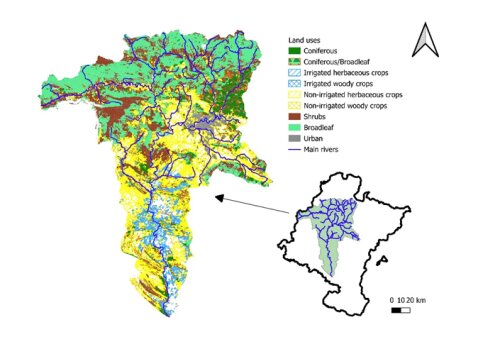

Human activity has left a deep imprint on the Arga. Historical records show irrigation systems and channelisation works dating back to Roman times. However, pressures intensified from the mid-20th century onwards with agricultural mechanisation, farmland consolidation, and the expansion of irrigation in the fertile floodplains of the lower basin. Water demand rose sharply, and flood and drought risks became chronic challenges [1]. Agriculture has been a key driver of change. The conversion of floodplains into cropland reduced the river’s capacity to buffer floods, while intensive cultivation increased dependence on irrigation and agrochemicals (Fig. 3). The widespread use of pesticides and fertilizers has led to nutrient and chemical inputs into both surface waters and groundwater, degrading water quality and threatening aquatic biodiversity. These pollutants also accumulate in soils and wetlands, undermining the ecological functioning of restored habitats. The combined agricultural and livestock impacts intensify eutrophication processes and contribute to the decline of sensitive species. Urban and industrial development around Pamplona, the capital of Navarre, has added further stressors. The expansion of impervious surfaces and infrastructure reduces infiltration, increases runoff, and fragments riparian zones. Industrial effluents and urban wastewater, even when treated, place additional burdens on the river’s assimilative capacity. Indeed, a study that analysed 38 European minks, 13 polecats (Mustela putorius Linnaeus, 1758), one American mink (Neogale vison (Schreber, 1777)) and 8 otters (Lutra lutra Linnaeus, 1758) found that all specimens were multi-contaminated with anticoagulants (bromadiolon), pesticides (Lindane, Endosulfan, DDDs and its metabolites and DDT metabolites), PCBs and heavy metals (mercury, lead, cadmium and arsenic) [2]. This highlights the impact of industrial, urban and agricultural impact on the food web. As a result, the Arga today reflects the cumulative effect of centuries of human use and decades of intensification, where hydrological alteration, diffuse and point-source pollution, and habitat loss interact to amplify the vulnerability of the basin (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Main land uses in the Arga basin.

Floods, droughts and hydromorphological change

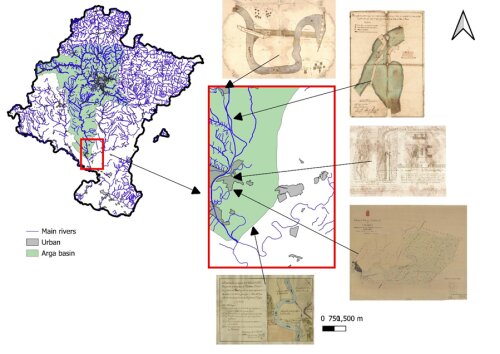

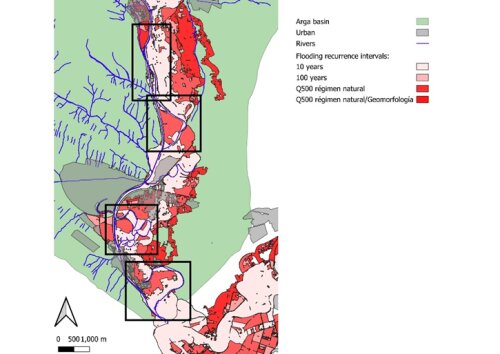

The intensification of agriculture in the lower basin also has profoundly altered the hydromorphology of the Arga River, leading to increased risks of both flooding and drought. In these areas, the conversion of natural floodplains into cropland has reduced the river’s natural ability to retain and slowly release water. Riparian vegetation clearance, land levelling, and the construction of drainage and irrigation systems accelerate runoff, decreasing the storage capacity of the floodplain and amplifying flood peaks [1]. At the same time, intensive cultivation and irrigation practices, which often raise groundwater levels and keep soils saturated, make the land less capable of absorbing heavy rainfall and more prone to water stress during dry periods. This dual effect has left the landscape increasingly vulnerable to extreme events, with more frequent and severe floods and prolonged droughts. Over the last centuries and more importantly, during the last decades, measures such as river straightening, channelisation, and the construction of dikes have been implemented in an attempt to mitigate flooding, and drought impacts through river straightening (Fig. 4 and annex). However, these interventions have not proved effective in mitigating the impacts of human activities in the basin, particularly in the most downstream towns (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Historical maps show works done in the Arga River centuries ago. The approximate location of the historical maps is provided, see the annex to observe the historical maps. Source: Archivo Real y General de Navarra, Gobierno de Navarra.

Figure 5. Flooding recurrence intervals are shown for the studied locations in the lower Arga.

Restoration actions and conservation focus

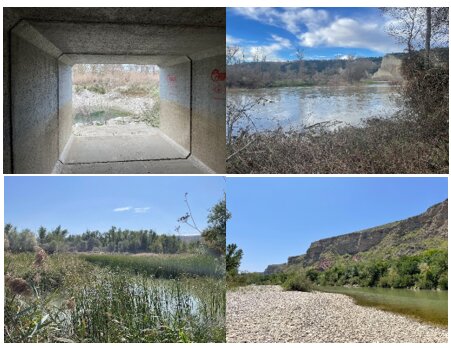

In response to the challenges, several projects have been carried out in the lower course of the Arga River by restoring former meanders and thereby dechannelizing the river. These actions aimed to re-establishing natural dynamics, reduce flood and drought risks, and enhance ecological functions. Four meanders are currently being restored: Soto de la Muga, Soto de Santa Eulalia, Soto de Gil y Ramal Hondo and Soto Sardilla (Fig. 6) [3, 4]. Works have included removing contaminated sediments, dismantling dikes, and restoring the floodplain at the confluence of the Arga and Aragón rivers. New pond-like wetlands were created to recover natural microtopography, and riparian forests were restored to improve habitat quality. Beyond ecosystem restoration, a central focus has been the conservation of the European mink, one of Europe’s most endangered mammals. The lower Arga hosts the largest remaining population in Western Europe, making this area critical for its survival [3].

Figure 6. Pictures showing the restored sites. From top-left and clock-wise: tunnel that connects the Arga River and Soto de la Muga’s meander, confluence between Arga and Aragón rivers after Soto Sardilla, the Arga river flowing next to Soto de la Muga and Soto de Gil y Ramal Hondo’s pond system.

What has been done

Building on this background, the RECHARGE project applies a whole-catchment approach to study the “water battery,” recognizing rivers as complex socio-ecological systems where biophysical processes and human activities are deeply interconnected. To do so, we analyse the added value that the implemented nature-based solutions (NbS) provide for the functioning and structure of the ecosystem, providing insights into the effects of restoration on river dynamics.

The research combines several layers of analysis:

- Foundations of the catchment (WP1): natural, anthropogenic, and climatic drivers that shape water availability and influence local communities.

- Spatiotemporal assessment (WP2): monitoring how NbS affect water quality, quantity, and ecosystem services.

- Indicator development (WP3): evaluating the potential of the water battery through metrics such as storage capacity, recharge and leakage, water use, impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services, and implications for EU policy (e.g., Water Framework Directive and Habitats Directive).

- Stakeholder engagement (WP4): designing participatory strategies with landowners, managers, conservation bodies, and local communities to strengthen resilience against extreme hydrological events.

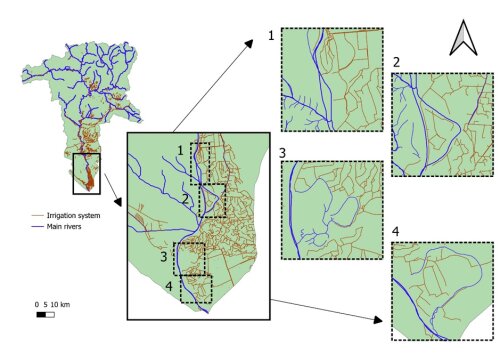

Within this framework, the University of the Basque Country team is focusing on one of the most complex tributaries of the Ebro River. Four study sites, each associated with a reconnected meander-wetland system, provide a unique Mediterranean-like floodplain setting. This landscape, long shaped by agriculture and settlement (Fig. 7), has undergone strong intensification in recent decades, increasing flood risk and exposing the system to irrigation surpluses, nutrient inputs, and encroachment on riparian zones. These conditions make it an ideal area to test how restoration and NbS can mitigate human-induced pressures while reinforcing the natural capacity of the water battery.

Figure 7. Irrigation system map and the four studied locations.

Literature

[1] Bescos, A. and Camarasa, A. M. (1998) – Estudios Geográficos – Caracterización hidrológica del río Arga (Navarra): El agua como recurso y como riesgo.

[2] https://territoriovison.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ii-taller-conservacion-vison-navarra.pdf

[3] https://territoriovison.eu/