Margot Luyckfasseel

A BAG OF CHIPS – AND WHAT IT TELLS ABOUT GHANA’S PAN-AFRICAN HISTORY

Centre for Urban History member Margot Luyckfasseel is currently in Accra for a 4-month research fellowship at the Merian Institute for Advanced Studies in Africa (MIASA), University of Ghana. In this blogpost she writes about how her experience in Accra introduces her to Ghanaian history in unexpected ways. Through a bag of chips for example.

‘Sticks in a bundle are unbreakable. Unite! – Bondei Proverb’ says the little paper in my bag of plantain chips, reminding me of Chinese fortune cookies. Admittedly, I have a soft spot for good packaging, so when I went grocery shopping in Accra Mall last week, I fell for the appealing design of a brand called Sankofa Snacks. As the package explains, ‘San-Ko-Fa is an ancient Akan proverb which tells us to TAKE THE BEST OF TRADITION TO GO FORWARD’. Two African proverbs in one bag. I am intrigued. The package also states that buying a bag of Sankofa chips equals ‘championing global black food culture.’ I am even more intrigued.

Some googling confirms my suspicion: this bag of chips opens up a whole world of African diaspora history. The founder of the brand is of Ghanaian-Lebanese-Liberian origin and obtained a degree in the US, after which he worked in corporate New York. Yet in 2016, he moved back to Ghana to launch Sankofa Snacks.

This man is not alone in his diasporic journey. In 2018, Ghana’s then President Nana Akufo-Addo officially launched the ‘Year of Return’ program, inviting African Americans to come to Ghana, in remembrance of the first enslaved Africans arriving in Virginia, USA. The program was a success, with about 750.000 visitors travelling to Ghana in 2019, most of them American. December, especially, known as ‘Detty December’, continues to be a popular month for tourists, with many cultural and nightlife events taking place.

Building on that success, the government extended the idea into ‘Beyond the Return’, a 10-year plan offering African Americans easier access to land and even citizenship. Framed as spiritual reconnection with the motherland, the program also stimulates the local economy. My Sankofa Snacks bag – with its careful blend of ancestral proverb and savvy branding – embodies that mix of heritage and entrepreneurship. And the audience is there: the African American Association of Ghana, founded in 1981, estimates that 10,000–15,000 African Americans currently live in the country.

Their presence, however, is not uncontested. A Reddit conversation about the question ‘How does the Ghanaian community feel about black Americans coming over in droves?’ illustrates the ambivalence. Many commentators argue that they are welcome to reconnect with their African roots as they contribute significantly to Ghana’s GDP. Others are less positive, arguing that ‘they are part of the reason houses in Ghana skyrocketed’. Others add that Americans do not know how to bargain: ‘They are truly hopeless at it. Indeed they are so bad that everything they touch becomes magnitudes more expensive for them and for everyone else: food, art, real estate.’ Someone else comments: ‘No problem at all. I love it. But absolutely NO SEGREGATION. This is not the USA or South Africa. If you are coming to live please integrate with the Ghanaians. The last thing I want is another Liberia’.

The reference to Liberia is telling. Separated from Ghana by Ivory Coast, the country’s past speaks directly to the history of African American return. In 1816, the American Colonization Society (ACS) was founded, at least partly in response to the growing group of free people of color and the fear they generated among slaveholders in the US. The idea was to repatriate them to the African continent to avoid slave rebellions. Yet these so-called Americo-Liberians came with their own American cultural references and did not mingle much with local African populations. They became an elite minority that held on to political power, declaring Liberia’s independence in 1847. Liberia’s postcolonial history, marred by economic dependency and political turmoil, is hardly a model anyone wishes to emulate today.

In comparison, Ghana has a more hopeful Pan-African history. Formerly known as the Gold Coast, Ghana was the first Sub-Saharan country to gain independence from its former European colonizer – Great Brittain – in 1957. Its president, Kwame Nkrumah, studied in the USA and organized the All-African’s People Conference in Accra in December 1958. Attended by prominent African intellectuals such as Patrice Lumumba, the conference channeled significant anti-imperialist efforts across the continent.

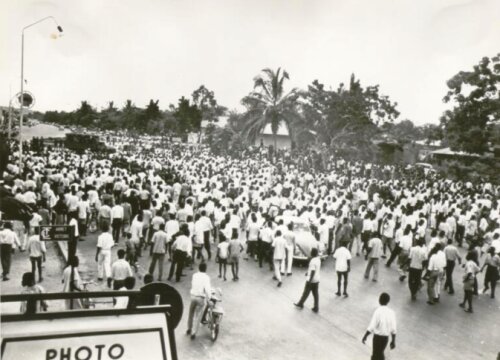

For the struggle for independence in the Belgian Congo, Nkrumah’s initiative indeed had direct consequences. Gaston Diomi, mayor of one of Léopoldville’s municipalities (today Kinshasa), attended the conference in Accra and was supposed to testify about his experience during a meeting of his political party, Alliance des Bakongo, on January 4, 1959. At the last minute, however, the colonial authorities of Léopoldville prohibited the meeting. As a result, people took to the streets, and made their demand for independence very explicit. Belgium, which claimed to govern a ‘model colony’, could no longer turn a blind eye to Congolese emancipation demands. A year later the country became independent.

Protests in Léopoldville, January 4 1959. (Photo: Belgian State Archives)

With Kwame Nkrumah’s explicit anti-imperial policy, Ghana became an attractive destination for Pan-Africanist thinkers early on. The prominent American Civil Rights activist and writer W.E.B. Du Bois spent his last years in Accra before his passing in 1963. He is buried in the Ghanaian capital, which is home to a memorial center in his name. In 2019, the management of the memorial was handed over to the W.E.B. Du Bois Museum Foundation in New York, which, according to its website, honors Du Bois legacy ‘by redeveloping and rebranding his final resting place in Accra’.

The appeal of Ghana for African Americans is hence not new. What is new is the scale of their presence. As in many places affected by mass tourism, the question is whether this will be a blessing or a curse for Ghanaians in the long run. If a Liberian scenario is to be avoided, African Americans and Ghanaians will have to work together and draw lessons from the past. In that sense, I cannot help but wonder if the Bondei proverb in my bag of Sankofa chips – unite! – is a direct reference to Nkrumah’s 1963 book Africa Must Unite.