Betting on the Next Pope ... in Antwerp in 1559

7/5/2025

Tekst in het Nederlands volgt onderaan.

On 22 April 2025, just a day after Pope Francis I’s death, the sports betting agency Ladbrokes offered to bet on who would become the next Holy Father and what papal name the new Bishop of Rome would take upon election. For betting agencies, papal elections constitute one of their biggest non-sports events. Now that the conclave is about to start, speculation is at its zenith. This betting has a long pedigree dating back until at least the sixteenth-century when Romans, often through Florentine brokers active in the Roman Banchi (from the Ponte Sant’Angelo and the Zecca Vecchia (the Old Mint) to the Church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini), gambled feverishly on the identity of the next pope and cardinals. Betting on the new cardinals was an annual event, while the election of a new Pontiff after the death of the former incumbent of the Holy See was of course a more random and thus an even more interesting event to bet on. In the following post I connect the urban histories of Rome and Antwerp and the events that took place in these cities during the sede vacante period in 1559 and I try to draw parallels with ongoing events.

Church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini in Rome, the epicenter of the Florentine Banchi neighborhood in the city, photo by the author in 2022.

How is this related to our Back to the Future project? Betting is clearly an action and a social practice in which ideas about and expectations for the future coalesce around a particular event. In betting on the new Bishop of Rome the bettors could (and did) use information and rumours about and coming out of the conclave to try and make money out of the papal election. In many cases, the bet relied on a careful assessment of balances of power within the Curia and the international politics that surely entered into the cardinals’ decision. Betting on a specific cardinal could also signify partisanship. In both cases, the act of betting gave the bettors so-called skin in the game, a financial stake in the outcome. Betting on the next pope was also a dynamic process since the end of the conclave was unknown. Therefore, the odds could change over time because of gossip and the betting behaviour of other players.

Gambling on the new Holy Father apparently reached far beyond the borders of Rome and the Italian peninsula. It is not a coincidence that the phenomenon also shows up in Antwerp in 1559, the focus of this blogpost. Antwerp had become one of the largest cities of commerce in Europe by that time and the large mercantile community in the Scheldt town was always hungry for the latest news. Combine that with one of the largest printing industries and you get a news hotspot. The Habsburg government was located in nearby Brussels and news and diplomats travelled at high speed between these two centers. The financial role of Antwerp for the Habsburg government turned Antwerp into a node in the network of international politics as well.

We know that Antwerp merchants and many others in the city were speculating in various financial enterprises, insurance, lotteries and bets on political events and the gender of unborn children. It is my research into lotteries that actually brought me to the 1559 papal betting in Antwerp. I was searching in the English State Papers Foreign: Elizabeth series for lotteries in England and the Low Countries when the following episode popped up on my screen.

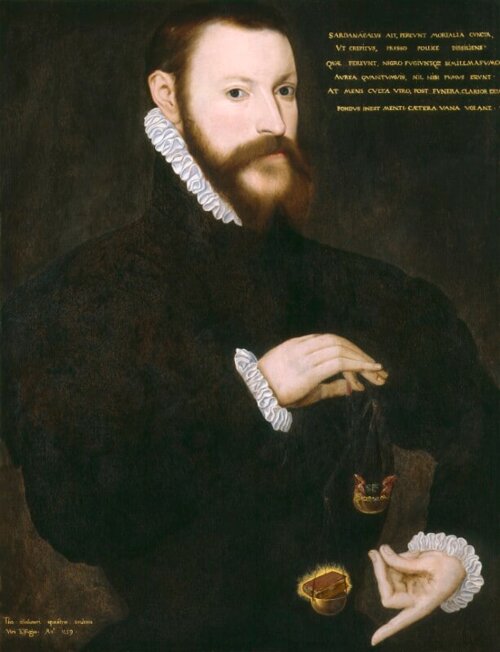

Sir Thomas Chaloner, by an unknown Flemish artist, oil on panel, 1559, National Portrait Gallery London, NPG 2445

On August 31 1559 Sir Thomas Chaloner, Queen Elizabeth I’s ambassador to King Philip II of Spain at Brussels, wrote from Brussels to Secretary of State William Cecil, Lord Burghley, about the news of the death of Pope Paul IV. In the morning of the day before Chaloner had received the news of the Pontiff’s death on August 18. So the news took twelve days to reach Brussels, quite fast by the speed standards of the time. Chaloner describes that all hell broke loose in Rome after Paul IV was summoned back to the Lord. The Roman people directed their fury – Paul IV was not very popular in Rome – at the Inquisition. Some letters received by Chaloner – so he received news from different sources – reported that the Chief Inquisitor was killed by the mob, according to other letters he was treated roughly and wounded. The mob also burned down all the records of the inquisition and set all the prisoners suspectos hereticæ pravitatis at large. One of these prisoners, according to Chaloner, was Thomas Wilson who Queen Elizabeth herself wanted to stand trial as a heretic in England but was in fact arrested and tortured in Rome by the Inquisition. Wilson later became Elizabeth’s Secretary of State. How futures could change! Another wild show of protest of the Roman crowds was the toppling of Pope Paul's statue on the Capitoline. The statue’s head served as a football for three days before it was thrown into the Tiber river. The events in the Vatican and Rome following the passing away of Pope Franciscus I were much more serene. Francis was in any case a more popular Holy Father compared to Paul IV and the Holy See was much more in charge than in 1559.

Pope Paul IV, c. 1560, after Jacopino Conte, Palazzo Ducale Mantova

In his letter, the English ambassador Chaloner then proceeds with details on the papabile, a term he uses and explains himself: “papabile (as they term it)”. One of the cardinals, Morone, is “papable” but he is also one of the prisoners released from the prison of the inquisition in the Castel Sant’Angelo. It is unlikely that his papal candidacy would survive further scrutiny. Cardinals Carpi (59 at the time), De Puteo (64), Mantua (Ercole Gonzaga, 53), and the Frenchman du Bellay (59 and Dean of the College of Cardinals) are mentioned as potential successors. Chaloner adds that they are considered too old to be eligible, while Cardinals Farnese and Ferrara, at 38 and 50 respectively, are deemed too young. Clearly, different age criteria than today.

The events following the death of a pope were extremely politically sensitive in the sixteenth century. Control over Rome and the Church was at stake — and this extended beyond the city itself, involving both religious and secular power in parts of Italy, Europe, and the European empires. At that time, all European monarchs sought to gather as much information as possible about the situation in Rome and actively tried to intervene in the decision-making process. Although the doors were closed, there were various ways to get small notes in and out of the conclave — for instance, through food deliveries or carrier pigeons. Numerous agents attempted to influence the voting behavior of cardinals, often through bribery. At this very moment, there are also attempts to discredit certain Cardinals by conservative Catholics, for example by publicizing the Philippine Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle singing of John Lennon's Imagine [there's no heaven] (see The ultra conservatives wanting to make the Vatican great again – POLITICO). And President Donald Trump has distributed an AI depiction of himself as pope (Trump criticised after posting AI image of himself as Pope).

The news about the death of Paul IV will not have been a total surprise to Chaloner. In a letter of August 16, Cecil already writes that he had heard “that all the French Cardinals go to Rome, saving the Cardinal of Tournay, for the choice of a new PP. (Pope), the old being near or dead”. A letter of August 8 from the ambassador to France Nicholas Throckmorton to Queen Elizabeth also reported on the departure of the French cardinals to Rome “as the last Pope is either dead or on the point of it". Throckmorton gives a list of papabili too: “One of these Cardinals, Carpi, Moroni, Sancta-Fiore [Guido Ascanio Sforza di Santa Fiora], or Ferrara shall have the election at this time to be Pope”. In an earlier letter (4 August), Throckmorton writes that if the French succeed in making the Cardinal of Ferrara the new successor of Saint Peter, that would be the worst-case scenario for the English Queen.

In any case, Chaloner was very keen on informing Cecil and Queen Elizabeth I about ongoing events in Rome and about possible futures concerning the papacy. This is obviously not a coincidence given the English throne’s troublesome relations with Rome and the major continental powers: France and the Habsburg Empire. If one of these powers were to manage to influence the Curia and the election, the papacy could become another pawn for them to move on the geopolitical playboard. Since the secession of King Henry VIII, Elizabeth's father, relations with Rome had been rather troubled. It therefore mattered greatly who would become pope. The spread of Protestantism and the growing tensions between Catholics and Protestants made the papacy an even more significant matter in the sixteenth century.

The Back to the Future project uses merchant letters, while I have relied on correspondence of government officials for this blog. These letters too are exercises in future thinking. Letters are time capsules since they arrive later, in the future, and thus describe events that have already taken place, but the addressee may not have been aware of them yet. These letters also include predictions, expectations and hopes, like the merchant letters.

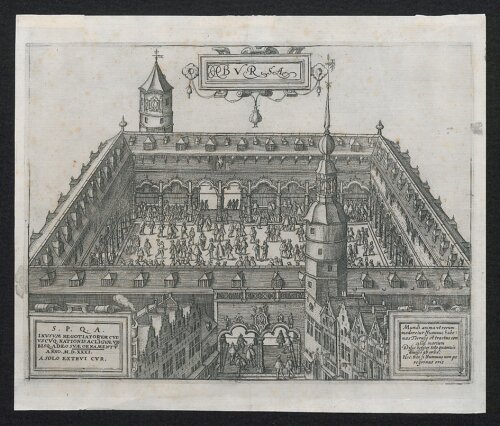

There is even more, and here we get to the betting on the next Bishop of Rome! In a post-scriptum to his letter, Chaloner added: “Upon the Bourse, the names of sixty-three Cardinals are set up in manner of a lottery at three crowns the head; whose chances upon him that shall be Pope shall win the lot. Some lay in lots for ten or twenty names, to be sure to light upon one.” The Bourse refers to Antwerp’s Bourse, for which a new building was constructed in 1532. The Antwerp Bourse as location for this betting enterprise was not an odd choice: it could accommodate a large number of persons, and it was already a place where speculation and games (dicing at the bourse was so often forbidden by the city authorities that it must have been a common event) took place.

The Antwerp Bourse, c. 1612-1648, Special Collections University of Antwerp. https://anet.be/record/opacuaobj/tg:uapr:665/E

This “lottery” and its mentioning in the PS of Chaloner’s letter of August 31 might mean that either the news had reached Antwerp sooner than Brussels or that the lottery was already set up before the news of Paul IV’s death had arrived in the Low Countries. Visitors of the Antwerp Bourse could participate in this lottery or betting initiative by paying three crowns for a bet on one out of 63 cardinals. Chaloner’s description is unfortunately a bit too short to answer the questions that I still have about this bet: if you get the name of the next pope right, how does the payout work? Did the winners have to share the collected funds? Equally? Or according to the number of tickets one had bought on the winning cardinal’s head? Chaloner notes at the end that some bettors certainly try to diversify their risk by betting on several cardinals. The number of 63 names is intriguing as well, since historical research has determined the number of papabili to be around fifty.

All this 1559 betting fever took place at the Bourse while it was actually forbidden according to the ordinances of the Antwerp city government. In 1510 an ordinance was issued in which gossip about the pope and the emperor and betting on all kinds of political events were prohibited. This was repeated in 1521 and in 1571 the Customary Law of Antwerp explicitly forbade the betting, insuring of the health, lives and voyages of important personalities.

The 1559 Conclave opened on September 5, only on December 26 was the new pope, Cardinal Giovanni Angelo de Medici di Marignano elected, the longest conclave of the sixteenth century. Neither Chaloner nor Throckmorton included him in their lists of papabili. If the upcoming conclave for the successor of Franciscus I takes this long, I promise to write a bit more on the future expectations that affected the 1559 conclave.

Further reading

There is very detailed research on the Sede Vacante of 1559 on Wikipedia and on this website: Sede Vacante 1559.

For recent and rich work on betting on the next pope in Italy and Rome I refer you to the following works by John M. Hunt, Nicholas Scott Baker and Renaud Villard:

"Betting on the Papal Election in Sixteenth-Century Rome" by John M. Hunt

The market in the conclave: Gambling on election outcomes in Renaissance Italy | Request PDF

The Vacant See in Early Modern Rome – A Social History of the Papal Interregnum | Brill

Le conclave des parieurs | Cairn.info

For more on the Back to the Future project: Back to the Future | Back to the Future | University of Antwerp

Nederlandstalige versie:

Wedden op de volgende paus ... in Antwerpen in 1559

Op 22 april 2025, een dag na de dood van paus Franciscus I, bood het Ladbrokes, een bedrijf gespecialiseerd in sportweddenschappen, de mogelijkheid om te wedden op wie de volgende Heilige Vader zou worden en welke pausnaam de nieuwe bisschop van Rome bij zijn verkiezing zou aannemen. Voor gokbedrijven vormen pausverkiezingen een van hun grootste niet-sportgerelateerde evenementen. Nu het conclaaf op het punt staat te beginnen, bereikt de speculatie haar hoogtepunt. Wedden op de volgende paus kent een lange geschiedenis die teruggaat tot minstens de zestiende eeuw, toen Romeinen – vaak via Florentijnse tussenpersonen die actief waren in de Romeinse Banchi (van de Ponte Sant’Angelo en de Zecca Vecchia (de Oude Munt) tot aan de kerk van San Giovanni dei Fiorentini) – koortsachtig gokten op de identiteit van de volgende paus en kardinalen. Wedden op nieuwe kardinalen was een jaarlijks terugkerend fenomeen, terwijl de verkiezing van een nieuwe paus na het overlijden van de vorige leider van de Heilige Stoel uiteraard meer willekeurig was, en daardoor nog interessanter was om op te wedden. In de volgende blogpost verbind ik de stadsgeschiedenissen van Rome en Antwerpen en de gebeurtenissen die plaatsvonden in deze steden tijdens de sede vacante-periode in 1559, en probeer ik parallellen te trekken met de actuele gebeurtenissen.

Wat heeft dit nu te maken met ons Back to the Future-project?

Wedden is duidelijk een handeling en een sociale praktijk waarin ideeën over en verwachtingen voor de toekomst samenkomen rond een specifiek evenement. Bij het wedden op de nieuwe bisschop van Rome konden (en kunnen) gokkers gebruikmaken van informatie en geruchten over het conclaaf of afkomstig uit het conclaaf om te proberen geld te verdienen aan de pausverkiezing. In veel gevallen was de inzet gebaseerd op een zorgvuldige inschatting van machtsverhoudingen binnen de Curie en de internationale politiek. Want speelden ongetwijfeld mee in de keuze van de kardinalen. Wedden op een specifieke kardinaal kon ook duiden op politieke of religieuze partijdigheid. In beide gevallen gaf het wedden de gokkers zogezegd skin in the game—een financieel belang bij de uitkomst. Wedden op de volgende paus was bovendien een dynamisch proces, aangezien het moment waarop het conclaaf zou eindigen onbekend was. Daardoor konden de kansen tijdens het conclaaf veranderen door roddels en het gokgedrag van andere spelers.

Gokken op de nieuwe Heilige Vader reikte kennelijk ver voorbij de grenzen van Rome en het Italiaanse schiereiland. Het is dan ook geen toeval dat dit fenomeen in 1559 ook opduikt in Antwerpen, het onderwerp van deze blogpost. Antwerpen was tegen die tijd uitgegroeid tot een van de grootste handelssteden van Europa en de omvangrijke koopmansgemeenschap aan de Schelde was voortdurend op zoek naar het laatste nieuws. Combineer dat met een van de grootste drukindustrieën van Europa, en je krijgt een echte nieuws-hotspot. De Habsburgse regering bevond zich in het nabijgelegen Brussel en nieuws en diplomaten reisden razendsnel tussen deze twee centra. De financiële rol van Antwerpen voor de Habsburgse overheid maakte van de stad bovendien een knooppunt in het netwerk van de internationale politiek.

We weten dat Antwerpse kooplieden, en vele anderen in de stad, speculeerden in allerlei financiële ondernemingen: verzekeringen, loterijen en weddenschappen op politieke gebeurtenissen en het geslacht van ongeboren kinderen. Het was mijn onderzoek naar loterijen dat mij uiteindelijk bracht bij de pauselijke weddenschappen in Antwerpen in 1559. Ik was in de English State Papers Foreign: Elizabeth-reeks op zoek naar loterijen in Engeland en de Lage Landen toen het volgende voorval op mijn scherm verscheen.

Op 31 augustus 1559 schreef Sir Thomas Chaloner, de ambassadeur van koningin Elizabeth I bij koning Filips II van Spanje in Brussel, vanuit Brussel aan de staatssecretaris William Cecil, Lord Burghley, over het nieuws van het overlijden van paus Paulus IV. Op de ochtend van de dag ervoor had Chaloner het bericht ontvangen over het overlijden van de paus op 18 augustus. Het nieuws had er dus twaalf dagen over gedaan om Brussel te bereiken, wat volgens de maatstaven van die tijd behoorlijk snel was. Chaloner beschrijft hoe in Rome de hel losbrak nadat Paulus IV tot de Heer was teruggeroepen. Het Romeinse volk richtte zijn woede – Paulus IV was niet erg populair in Rome – op de Inquisitie. Uit sommige brieven die Chaloner ontving – hij kreeg dus informatie uit verschillende bronnen – bleek dat de opperinquisiteur door de menigte werd gedood; volgens andere berichten werd hij ruw behandeld en verwond. Het Romeinse gepeupel stak ook de archieven van de Inquisitie in brand en liet alle gevangenen die verdacht werden van ketterse verdorvenheid (suspectos hereticæ pravitatis) vrij. Een van die gevangenen was volgens Chaloner Thomas Wilson, die koningin Elizabeth persoonlijk als ketter wilde laten berechten in Engeland. Hij werd in Rome door de Inquisitie gearresteerd en gemarteld. Wilson werd later zelf staatssecretaris van Elizabeth. Wat kunnen toekomsten toch veranderen!

Een andere wilde en symbolische protestactie van de Romeinse menigte was het omver halen van het standbeeld van paus Paulus op het Capitool. De kop van het beeld werd drie dagen lang als voetbal gebruikt, waarna de kop in de Tiber werd gegooid. De gebeurtenissen in het Vaticaan en Rome na het overlijden van paus Franciscus I verliepen veel rustiger. Franciscus was hoe dan ook een populairdere paus dan Paulus IV en de Heilige Stoel had in 2025 aanzienlijk meer controle dan in 1559.

In zijn brief gaat de Engelse ambassadeur Chaloner verder met details over de papabili, een term die hij zelf gebruikt en ook uitlegt: “papabile (zoals men het noemt)”. Een van de kardinalen, Morone, wordt als papabile beschouwd, maar hij is tevens een van de gevangenen die uit de gevangenis van de inquisitie in de Engelenburcht (Castel Sant’Angelo) zijn vrijgelaten. Het is onwaarschijnlijk dat zijn pauselijke kandidatuur verdere toetsing zou doorstaan. De kardinalen Carpi (toen 59 jaar), De Puteo (64), Mantua (Ercole Gonzaga, 53), en de Fransman Du Bellay (59 en decaan van het College van Kardinalen) worden genoemd als mogelijke opvolgers. Chaloner voegt toe dat zij als te oud worden beschouwd om in aanmerking te komen, terwijl de kardinalen Farnese en Ferrara, respectievelijk 38 en 50 jaar, als te jong worden gezien. Overduidelijk golden er destijds andere leeftijdscriteria dan nu. De gebeurtenissen na het overlijden van een paus waren in de zestiende eeuw politiek uiterst gevoelig. Het ging om de controle over Rome en de Kerk — en die reikte verder dan de stad zelf, tot aan religieuze én wereldlijke machtsstructuren in delen van Italië, Europa en de Europese koloniale rijken. Alle Europese vorsten probeerden in die tijd zoveel mogelijk informatie te verzamelen over de situatie in Rome en trachtten actief invloed uit te oefenen op het besluitvormingsproces. Hoewel de deuren van het conclaaf gesloten waren, waren er verschillende manieren om kleine briefjes binnen en buiten te krijgen — bijvoorbeeld via voedselbezorging of postduiven. Tal van agenten probeerden het stemgedrag van kardinalen te beïnvloeden, vaak via omkoping.

Ook op dit moment zijn er pogingen om bepaalde kardinalen in diskrediet te brengen, bijvoorbeeld door conservatieve katholieken. Denk aan het publiceren van een video waarop de Filipijnse kardinaal Luis Antonio Tagle Imagine van John Lennon zingt ("no heaven") (zie The ultra conservatives wanting to make the Vatican great again – POLITICO) of aan het feit dat president Donald Trump een AI-gegenereerde afbeelding verspreidde waarop hij zelf als paus is afgebeeld (Trump criticised after posting AI image of himself as Pope).

Het nieuws over het overlijden van Paulus IV zal voor Chaloner waarschijnlijk geen totale verrassing zijn geweest. In een brief van 16 augustus schrijft Cecil al dat hij had gehoord “dat alle Franse kardinalen naar Rome gaan, behalve de kardinaal van Doornik, voor de keuze van een nieuwe PP (Paus), de oude zijnde nabij de dood of reeds overleden.” Een brief van 8 augustus van ambassadeur Nicholas Throckmorton in Frankrijk aan koningin Elizabeth meldde ook dat de Franse kardinalen naar Rome vertrokken “aangezien de laatste paus dood is of op sterven ligt”. Throckmorton geeft daarin een lijst van papabili: “Een van deze kardinalen, Carpi, Moroni, Sancta-Fiore [Guido Ascanio Sforza di Santa Fiora], of Ferrara zal dit keer verkozen worden tot paus.” In een eerdere brief (4 augustus) schrijft Throckmorton dat als het de Fransen lukt om de kardinaal van Ferrara tot opvolger van Petrus te maken, dat het slechtste scenario zou zijn voor de Engelse koningin.

Hoe dan ook, Chaloner was er zeer op gebrand om Cecil en koningin Elizabeth I op de hoogte te houden van de gebeurtenissen in Rome en van mogelijke toekomsten met betrekking tot het pausdom. Dat is uiteraard geen toeval, gezien de problematische relatie van de Engelse troon met Rome en met de grote continentale machten: Frankrijk en het Habsburgse Rijk. Als een van deze machten erin zou slagen invloed te krijgen op de Curie en de pausverkiezing, zou het pausdom voor hen een geopolitieke pion kunnen worden. Sinds de afscheiding van koning Hendrik VIII, de vader van Elizabeth, waren de relaties met Rome gespannen. Het deed er dus toe wie paus zou worden. De verspreiding van het protestantisme en de groeiende spanningen tussen katholieken en protestanten maakten het pausdom in de zestiende eeuw politiek nog belangrijker.

Het Back to the Future-project gebruikt brieven van kooplieden, terwijl ik voor deze blogpost heb gewerkt met correspondentie van overheidsfunctionarissen. Ook deze brieven zijn oefeningen in toekomstdenken. Brieven zijn tijdscapsules: ze arriveren later, in de toekomst, en beschrijven dus gebeurtenissen die al hebben plaatsgevonden, maar waarvan de ontvanger mogelijk nog niet op de hoogte was. Ze bevatten ook voorspellingen, verwachtingen en hoop – net zoals de brieven van kooplieden.

En er is meer: de weddenschappen op de volgende Pontifex Maximus in Antwerpen! In een postscriptum aan zijn brief voegde Chaloner het volgende toe: “Op de beurs worden de namen van drieënzestig kardinalen uitgehangen, als een soort loterij, aan drie kronen per naam; wie de juiste kandidaat kiest, wint de loterij. Sommigen zetten in op tien of twintig namen, om er zeker van te zijn dat ze er een goed hebben.” Beurs verwijst naar de Antwerpse beurs, waarvoor in 1532 een nieuw gebouw werd opgetrokken. De Antwerpse beurs was geen vreemde keuze voor deze gokpraktijk: ze bood plaats aan een groot aantal mensen en was al een plek waar speculatie en kansspelen plaatsvonden (dobbelspelen op de beurs werden zo vaak door de stadsautoriteiten verboden dat ze kennelijk heel gebruikelijk waren).

Deze “loterij” en de vermelding ervan in het postscriptum van Chaloner’s brief van 31 augustus kunnen betekenen dat het nieuws Antwerpen eerder had bereikt dan Brussel, of dat de loterij al was opgezet voordat het nieuws over de dood van Paulus IV in de Lage Landen was aangekomen. Bezoekers van de Antwerpse Beurs konden deelnemen aan deze loterij of gokinitiatief door drie kronen in te zetten op een van de 63 kardinalen. De beschrijving van Chaloner is helaas te kort om de vragen die ik nog heb over deze weddenschap te beantwoorden: als je de naam van de volgende paus goed hebt, hoe werkt de uitbetaling dan? Moesten de winnaars de verzamelde fondsen delen? Evenredig? Of volgens het aantal tickets dat men had gekocht op de naam van de winnende kardinaal? Chaloner merkt aan het einde op dat sommige gokkers zeker proberen hun risico te spreiden door op meerdere kardinalen in te zetten. Het aantal van 63 namen is ook intrigerend aangezien historisch onderzoek heeft vastgesteld dat het aantal papabili rond de vijftig ligt.

De gokkoorts van 1559 vond plaats in de Beurs, terwijl gokken volgens de verordeningen van de Antwerpse stadsregering illegaal was. In 1510 werd een verordening uitgevaardigd waarin roddelen over de paus en de keizer en het gokken op allerlei politieke gebeurtenissen werd verboden. Dit verbod werd herhaald in 1521, en in 1571 verbiedt het Antwerpse gewoonterecht expliciet het gokken op en het verzekeren van de gezondheid, de levens en reizen van belangrijke personen.

Het conclaaf van 1559 opende op 5 september, maar pas op 26 december werd de nieuwe paus gekozen, de kardinaal Giovanni Angelo de Medici di Marignano, Pius IV, het langste conclaaf van de zestiende eeuw. Noch Chaloner noch Throckmorton noemden hem in hun lijsten van papabili. Als het komende conclaaf voor de opvolger van Franciscus I zo lang duurt, beloof ik meer te schrijven over de toekomstverwachtingen die het conclaaf van 1559 beïnvloedden.