In collaboration with the Study Advice and Student Counselling Services and the Education Department (Quality assurance and innovation & Policy and organisation) at the University of Antwerp.

1. Introduction

The time given to students to complete a written exam can have an impact on their performance (Tarchinski et al., 2022). However, when the amount of time allowed doesn’t reflect the content of the exam (length, difficulty level, etc.), then the emphasis may unintentionally be on speed or the student’s ability to cope with stress rather than on demonstrating the knowledge, skills and attitudes acquired. The exam then becomes invalid because it fails to provide a realistic representation of the student's mastery of the learning content (Birkhead, 2018; ECHO Teaching Tip Quality of Assessment, November 2024). Moreover, this can lead to stress, frustration and reduced performance among students. Certain groups of students are more severely hampered by this, for example students with a functional impairment, non-native speakers, students with a difficult domestic situation and those students providing informal care at home. So, to ensure these students also have a fair chance, correctly estimating exam time is essential.

But how much time is best? And how exactly does time play a role? Plus, does it apply to all students? In this teaching tip, we provide you with practical tools to correctly estimate the exam time for your programme component so that students have enough space to demonstrate their acquired competences during the assessment.

2. How do you make a realistic estimate?

Estimating the exam time for your programme component is no easy task. Indeed, the ideal time for a student depends on several factors, including the type of exam questions, the number of questions, and their difficulty. Below is a step-by-step plan to make the most realistic estimate possible.

STEP 1 - Define the format and content of the exam

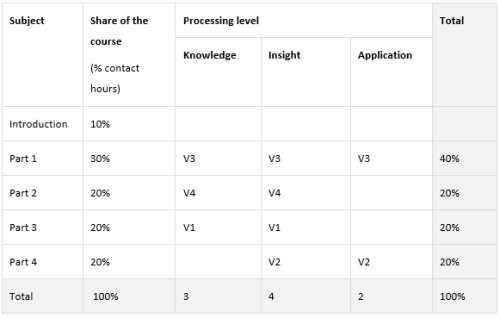

To determine what should ideally be covered in your exam, start from the final competences you’ve set. Make sure your questions are balanced across these final competences as well as across the learning content you want to assess. Note that if a particular final competence is essential in your programme component, this should be reflected in the weighting of the exam questions. To design a well-balanced exam, you can use an assessment matrix (ECHO Education Tip 2013, Measure what you need to measure; KU Leuven, 2025). Such a matrix helps relate the final competences, learning content and processing levels (Harting et al., 2019) to each other to determine how many exam questions each section should contain. Below is an example of an assessment matrix: it shows in each case how many questions are covered per content section and per processing level You can derive the processing level from your final competences. (Note that this is just one example; other variants are possible.)

By using this test matrix, you now have a draft of your exam and can start looking at how much time the student will need.

STEP 2 - Make an estimate of the time it will take a student to complete your exam.

Now estimate the standard time you think a student needs on average to take the exam.

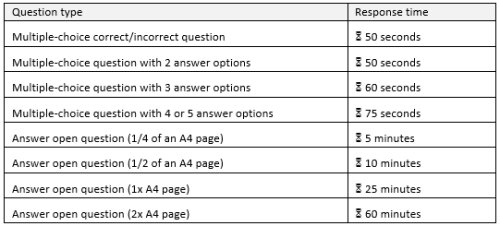

- The following guidelines will give you an idea of the response time for each question type (Van Berkel et al., 2017).

In open-ended questions, time doesn’t increase proportionally with the length of the answer. After all, the longer the answer, the more the student is expected to provide interconnections and pay extra attention to structure.

- Keep in mind the cognitive level of the question. The more difficult the question, the more time you should provide. For example, when you ask students to develop an argument based on different theories or choose the right model to solve a new problem, you have to provide more time than if you ask them to describe a familiar theory or work through a known mathematical proof.

- Complete your own exam and multiply the time required by four. Then, add 10 to 15 minutes for reviewing the exam and add time to read the instructions (Van Petegem et al., 2013).

- Ask a colleague who’s not connected to the assessment/study programme to take the exam and estimate the time needed (the four-eyes principle). That way, you have an extra pair of eyes and an extra check.

- Be sure to also check the maximum time allowed by your institution: at UAntwerp, for example, there’s a maximum of four hours for a written exam and one hour for an oral examination.

STEP 3 - Afterwards, check whether your time estimate was realistic and make adjustments if necessary.

Check how much time students actually use to work on their exams.

- Project a digital clock (with numbers) so that students can monitor the time themselves during the exam (see Infofiche UAntwerpen [in Dutch] after logging in).

- When handing in their exams, ask students to note the time they submit their paper.

- If we assume that education is designed inclusively, you can distinguish between standard time, extra time and total or inclusive time. Standard time is the standard scheduled time for taking an exam. Extra time is about 30% extra time over and above the standard scheduled time for taking an exam. The total or inclusive time is the sum of the standard time and the 30% extra time. Teachers who offer 30% extra time on top of the standard time for all students are therefore providing an inclusive exam time.

Have students note their time in different colours:

* students submitting within 70% of standard time note their time in black

* students submitting between 70% and 100% of standard time note their time in green

* students submitting after the standard time note their time in blue.

Based on this time data, you can can then judge whether your exam time is generous or quite tight.

- If 70% or more of students take the exam within 70% of the standard time, this shows the exam time may be generous enough.

- If a large proportion of students take between 70% and 100% of the standard time, this is a sign that the standard exam time is probably on the tight side. In that case, you might consider extending the exam time or cutting the content of the exam. Make sure that your exam remains valid (make sure that the assessment is geared towards the competences you’ve set) and reliable (limit random factors and measuring errors as much as possible) ECHO Teaching Tip Quality testing, November 2024).

- Finally, compare the number of students who submitted after the standard time with the number of students who applied for special facilities. No one needed longer than the standard time? Then that's a sign that your exam is already set up very inclusively! If the number is less than the number of students with the special facility, then the standard time is probably already more than enough.

- For more practical guidelines on inclusive exam time, see the UAntwerp document 'Inclusive examination time' (accessible to UAntwerp staff members after logging in).

3. Extra time as a special examination facility

Since education is often not organised inclusively, some students experience difficulties in demonstrating their knowledge and skills during assessments. These include, for example, students with a functional impairment, and students with working, artist or top athlete status. To help balance these difficulties, special measures ('special facilities1') have been introduced in many higher education institutions, removing unnecessary barriers for students (Vidal Rodeiro & Macinska, 2022).

Granting extra exam time is one of the most requested and granted facilities among students with a functional impairment (Van Hees, Stokx, & Willems, 2024). This facility can be granted for various reasons, for example because students read or write more slowly, because they process information more slowly than other students do, or because they lose concentration quickly.

At UAntwerp, a student awarded this facility will be given 30% extra time, with the exam as a whole never exceeding four hours. At other institutions in Flanders and the Netherlands, this percentage is often also around 25-30%. A review by Harrison, Pollock and Holmes (2022) found that students with learning difficulties in particular would benefit from up to 25% extra exam time. Their study suggests that 25% extra time may be justified in exceptional situations, but should be carefully considered using an established decision-making model.

1 Support for students with a functional impairment is outlined in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2009) and is supported by legislation. According to Article II.276, Paragraph 3 of the Higher Education Code, students with a functional impairment are entitled to reasonable accommodations in order to ‘participate in higher education on an equal basis with other students’.

4. Extra exam time for everyone?

International research on the effectiveness of extra exam time and its impact on student performance, both with and without a functional impairment, does not currently offer a consistent conclusion (Duncan & Purcell, 2020; Sokal, 2017). For example, some studies suggest that both students with and without a functional impairment achieve higher scores when they have more time, with the advantage generally being greater for students with a functional impairment (Sireci et al., 2005). Other studies suggest that both groups benefit equally from extra exam time (Cahan et al., 2016; Lovett, 2010). Other studies, however, report no significant effect for either group (Jansen et al., 2018).

Research into students' perceptions shows similar results. In several studies, students with a functional impairment clearly indicate that they consider extra exam time to be effective (Emmers et al., 2015; Jansen et al., 2016; Lovett & Leja, 2013). Knowing they have this extra time reduces pressure and stress. In fact, often, students don’t take advantage of the extra exam time allocated, as the removal of the time pressure is enough for the student to complete the examination calmly within the extra allotted time (ECHO Education Tip 2019 Special facilities and exams).

Since there is no evidence that any particular group is disadvantaged when all students are given extra exam time, and because we mainly want to test students' knowledge, skills and attitudes and not their stress resistance, introducing extra time for all can be a worthwhile step. It not only promotes inclusiveness within the institution (Van Hees et al., 2024), but also lowers the administrative burden: students no longer have to apply for a separate statute when claiming extra examination time and teachers have to deal with fewer additional special requests and procedures. This creates a fairer and less stressful exam experience, allowing students to focus better on the content. After all, there are now also target groups that are left out, as they’re not entitled to special facilities. These are the students who don’t receive a diagnosis for financial reasons or because of waiting lists, students with a difficult home situation, students acting as carers at home, etc.

The key distinction, however, is that this measure (extra exam time for all) is only suitable when time pressure is not an essential part of the final competences being assessed, which may be the case in some professional contexts, such as nursing or medicine, for example. What’s more, it’s important to systematically monitor students' real time requirements (as suggested in §2, step 3) so that exams don’t take longer than necessary for a valid assessment. Finally, keeping up-to-date with scientific research on the effectiveness and optimisation of exam time is essential, so that we can further tailor our exams to the needs of students and thus further improve their validity.

Want to know more?

ECHO Education tips

- Quality of assessment (2024)

- Bijzondere faciliteiten en examens (2019; only in Dutch)

- Measure what you need to know (2013)

KU Leuven (2025). Infofiche Toetsmatrijs. Dienst Onderwijsprofessionalisering en -Ondersteuning. Geraadpleegd op 1 september 2025, van https://www.kuleuven.be/onderwijs/evalueren/documenten/toetsmatrijs.pdf (Only in Dutch)

Birkhead, S. (2018). Testing Off the Clock: Allowing Extended Time for All Students on Tests. Journal of Nursing Education. 57(3):166-169. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20180221-08

Cahan, S., Nirel, R., & Alkoby, M. (2016). The extra-examination time granting policy: A reconceptualization. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 34(5), 461–472

Duncan, H., & Purcell, C. (2020). Consensus or contradiction? A review of the current research into the impact of granting extra time in exams to students with specific learning difficulties (SpLD). Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(4), 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1578341

Emmers, E., Mattys, L., Petry, K., & Baeyens, D. (2015). OBPWO Eindrapport: Inclusief hoger onderwijs: Multi-actoren, multi-methode onderzoek naar het aanbod en het gebruik van ondersteuning voor studenten met een functiebeperking. (Only in Dutch)

Harrison, A., Pollock, B., & Holmes, A. (2022). Provision of extended assessment time in post-secondary settings: A review of the literature and proposed guidelines for practice. Psychological Injury and Law, 15(3), 295–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12207-022-09451-3

Harting, L., Apikian, G., & Dijkstra, W. (2019). Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy for Learning Objectives.

Jansen, D., Petry, K., Ceulemans, E., van der Oord, S., Noens, I., & Baeyens, D. (2016). Functioning and participation problems of students with ADHD in higher education: which reasonable accommodations are effective? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2016.1254965

Jansen, D., Petry, K., Evans, S., Noens, I., & Baeyens, D. (2018). The Implementation of Extended Examination Duration for Students With ADHD in Higher Education. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(14), 1746-1758. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054718787879

Lovett, B. J. (2010). Extended Time Testing Accommodations for Students with Disabilities: Answers to Five Fundamental Questions. Review of Educational Research, 80(4), 611-638. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654310364063 (Original work published 2010)

Lovett, B., & Leja, A. (2013). Students’ perceptions of testing accommodations: What we know, what we need to know, and why it matters. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 29(1), 72–89.

Sireci, S., Scarpati, S., & Li, S. (2005). Test accommodations for students with disabilities: An analysis of the interaction hypothesis. Review of educational research, 75(4), 457-490. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075004457

Sireci, S., Li, S., & Scarpati, S. (2003). The effects of test accommodations on test performance: A review of the literature. Research Report No. 485. Center for Educational Assessment, School of Education, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Geraadpleegd op 1 september 2025, van https://nceo.umn.edu/docs/onlinepubs/testaccommlitreview.pdf

Sokal, L., & Wilson, A. (2017). In the Nick of Time: A Pan-Canadian Examination of Extended Testing Time Accommodation in Post-secondary Schools. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 6(1), 28–62. https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v6i1.332

Tarchinski, N., Rypkema, H., Finzell, T., Popov, Y., & McKay, T. (2022). Extended exam time has a minimal impact on disparities in student outcomes in introductory physics. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 7, p. 831801). Frontiers Media SA.

van Berkel, H., Bax, A., & Joosten-ten Brinke, D. (2017). Toetsen in het hoger onderwijs. (4 ed.) Bohn Stafleu van Loghum. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-368-1679-3 (Only in Dutch)

Van Hees, V., Stokx, R., & Willems, K. (2024). Inclusieve onderwijs- en evaluatiemaatregelen: van beleid naar praktijk. Gent: Steunpunt Inclusief Hoger Onderwijs. (Only in Dutch)

Van Petegem, P., Geyskens, J., Stes, A., Van Waes, S., & Verdurmen, C. (2013). Vijftig onderwijstips. Antwerpen: Garant. (Only in Dutch)

Vidal Rodeiro, C., & Macinska, S. (2022). Equal opportunity or unfair advantage? The impact of test accommodations on performance in high-stakes assessments. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 29(4), 462–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2022.2121680

For UAntwerp staff (after logging in)

- Inclusieve examenmaatregelen aan UAntwerpen (Only in Dutch)