What is student workload?

Study load or student workload refers to the total time investment that an average student* needs to achieve the learning outcomes of a course. This includes timetabled contact hours (lectures, tutorials, practicals, etc.), and also time for practising the learning content through self-study, (group) assignments, preparing lessons, studying for and taking the exam, etc. (Pogacnik et al., 2004; Souto-Iglesias & Baeza-Romero, 2018). In Flanders, this student workload is expressed in credits (ECTS), where one credit stands for 25 to 30 hours of teaching and other study activities (Structural Decree, 2003). In other words, if a course counts for 3 credits, you have to provide a total of 3 x 25-30 hours = 75-90 hours of teaching and study time.

The term 'studyability' is often mentioned in the same breath as student workload. Although the two concepts are closely linked, studyability encompasses more than just the amount of teaching and study time. Factors such as the difficulty of the course, the scope of the subject matter and the students' prior knowledge also play a role. In this teaching tip, we focus specifically on student workload and help you be able to estimate it as realistically as possible.

Actual versus perceived student workload

Before you start planning and designing your teaching, it’s important to know that in addition to objective or actual student workload - such as the number of hours an assignment or course should officially take according to the number of credits - there’s also such a thing as students' perceived student workload (Kyndt et al., 2014). Indeed, students don’t always experience their workload as it’s intended on paper. So, mind the gap! Factors such as unclear instructions, a build-up of deadlines, or uncertainty about expectations can significantly increase the perceived student workload (Impola, 2024; Kember, 2004), even if the actual time investment is reasonable. Of course, personal factors, such as ability, motivation and effort, can also play a role in this (Bowyer, 2012). However, students who experience overload are unable to learn efficiently and have positive learning experiences (Karjalainen et al., 2006). As a teacher, you obviously can’t deal with every subjective perception, but it’s good to keep in mind that it has an impact on your students' learning performance.

The good news is, according to Kyndt et al. (2014), you can reduce students' perceived workload without actually reducing the amount of work required. You can do this, among other things, by communicating clearly about expectations, timing assignments well, leaving room for feedback, etc. This is basically related to the concept of constructive alignment (Biggs, 1996): first think about what goals you have in mind, about the teaching method you can best use to achieve them and what form of evaluation is most suitable to evaluate your goals; and then communicate this clearly to the students. This way, you help them perceive the learning process as manageable and meaningful - which ultimately improves the effectiveness of your teaching (Thornby, Brazeau & Chen, 2023).

Estimating student workload

Getting started: you’re teaching a course for the first time and you want to estimate how many assignments you can give, which deadlines you can schedule and how much contact time it’s best to provide. Or: you want to rework your course for next academic year and in the process want to balance the study load more? Below is a roadmap.

- Your course may have already been assigned some credits from the programme. Check what this number is and calculate what this means for the total study load in hours.

For example: A 6-credit course unit has a total study load of 150 to 180 hours (6x25 to 6x30).

- Divide these hours between the various teaching activities you’ll offer and the corresponding study time you expect students to spend.

- First check with your education/programme committee whether there are guidelines in terms of contact time for e.g. lectures, seminar/work seminars, practicals, internship, etc. in relation to the number of credits of the entire course unit.

For example: In UAntwerp's Faculty of Pharmaceutical, Biomedical and Veterinary Sciences, they use the following guidelines in terms of contact hours that can be scheduled for 1 credit: 7.5h lecture or 12h seminar/workshop or 20h practicals or 30h for internship. The self-study expected of students - additional to these contact hours - must then be added on.

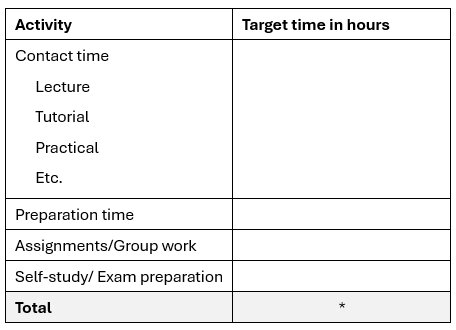

- Then, for each teaching/study activity, estimate how much time you would allocate for the different components (contact time, preparation time, time for making assignments, etc.). For this, you can use the table below. Keep in mind that students will need significantly more time to process a part of a lecture or complete an assignment than you as an expert on the subject.

*Make sure this number matches the number of hours you have available for your course according to the credits (e.g. for 3 credits, this is 75 to 90 hours).

- Check with your colleagues: how do they estimate the student workload for their course for the above categories? Have them take a look at your schedule if necessary. This will help you make a realistic estimate, and what’s more, it will give you more insight into the total student workload expected of students across course units.

- You now have a rough idea of how much time students will spend on average on the different components of your course. Now take a calendar of the semester in which your course runs and specify your estimate in terms of teaching/study activities, (sub)assignments and deadlines. Aim for a balanced division of work and test your deadlines by level of study programme. That way, you avoid any overlapping deadlines. In your opinion, do students have enough time and breathing space to process everything? With that done, your planning is now complete!

Monitoring student workload

As soon as your course has started, it’s a good idea to ask the students in the meantime how the processing of, for example, the material, the assignments, the exercises is going. Ask about the causes of a high perceived workload, so that you know whether you need to adjust the actual study load (number of assignments, extending deadlines, etc.) or whether you need to focus more on, for example, communication or motivation of the students. That way, you stay well informed and can make timely adjustments where necessary.

At the end of the semester, evaluate whether your estimate of student workload was realistic. Below are some options that can help you with this. Ideally, you should combine several of the methods below to get a clear picture of the student workload in your course.

Online student survey

Perhaps your institution's online student assessment/teacher evaluation includes some questions that refer to student workload. At UAntwerp, for example, the following items are involved, respectively for lectures and practicals: ‘The teacher's expectations of what we needed to know and be able to do were realistic and achievable.’ and ‘On average, how much time did you spend preparing for the practical?’

Focus groups

It might be the case that focus groups are also organised periodically within your faculty/study programme. During such a focus group, a policy officer discusses the quality of education (including the student workload) together with a representative group of students from a certain phase of the study programme.

Short, targeted survey

You yourself can organise a short, targeted survey (via Microsoft Forms, BB, etc): In this type of questioning, you can very specifically address questions such as ‘How many hours per week on average did you spend on this subject?’, ‘In your opinion, did this match with the number of credits?’ or ‘Which parts were the most/least time-intensive?’. Keep it short and, if necessary, share the results afterwards so students know you’re making use of them.

Reflection during the last lesson

You can also opt for a moment of reflection during the last lesson: where you discuss the student workload with the students. You may then do a short round of written feedback first, asking everyone to note something down, and then talk more in detail about the answers.

Data

Make an analysis of students' average scores for certain assignments, the exam, etc., and chart the ratio of those who fail to those who pass. At UAntwerp, course coordinators (and co-coordinators) can also check the correlation between students' scores on a course and the student's overall average score. This will also give you an insight into the extent to which the scores achieved for your course differ from the rest of the programme. Plus, you can also get an idea whether or not your course is perceived as too heavy or too light.

Measuring 'actual' student workload

Want to go one step further and take a measurement that approximates the actual student workload as closely as possible? Well, this isn’t straightforward, as it requires a lot of effort from students (and also therefore for you as a teacher to get a high enough response rate) and it’s impossible to separate it completely from the perceived student workload (see §2).

However, setting up a way to measure study time may be necessary when a major change to the curriculum or to your course unit is planned, the number of credits of your course changes, or when the teaching evaluation identifies a problem with the student workload.

Below we outline some possible methods you can use, each with their advantages and disadvantages (Marshall, 2018; KU Leuven, 2025; UAntwerp, 2021). At UAntwerp, the three ways of measuring study time can be automated so that students are invited via e-mail or Blackboard to take part, they can record their study time data electronically, and the results are processed quickly.

Time-tracking

Here, for example, every week students estimate the time spent on the course.

- Advantage: most accurate estimate due to fast registration (time spent is still fresh in their minds)

- Disadvantage: requires a lot of effort from students, keeping the response rate sufficiently high isn’t obvious, the response rate may not be representative of the whole group (but only of the type of student committed to doing this)

Retrospective estimates

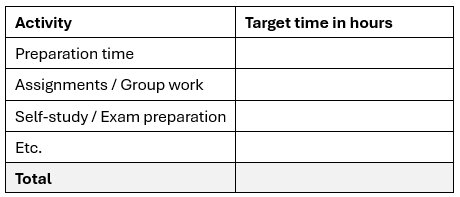

In this method, after the course is completed and thus after the exam, students estimate how much time they spent on the different parts of the course (preparation, assignments, self-study, etc.) based on this table, for example.

- Advantage: requires less effort from students than time-tracking, gives a more general picture

- Disadvantage: possible recall errors (over- or underestimation), socially desirable answers

Pairwise comparison

In this method, students are offered pairs of courses and indicate which one has the highest student workload. Based on this, the courses are ranked from light to heavy. This method is often combined with time recording in single courses to determine the absolute study time of all courses.

- Advantage: minimum effort, suitable for larger groups of students

- Disadvantage: less reliable, useful when combined with another method

Conclusion

In summary, estimating student workload is not an exact science, but it is an important consideration when designing your course. Indeed, both the actual and perceived workload influence how students experience the learning process and, consequently, their learning outcomes. Small adjustments in communication, phasing and alignment can already make a big difference. Regular questioning and adjustment help keep the student workload realistic and achievable, thus contributing to a more effective student learning experience.

*The average student is defined here as the student who passes within the stipulated duration of study (Structural Decree, 2003).

Want to know more?

Biggs, J.B. (1996) Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment, Higher Education, 32, 1–18.

Bowyer, K. (2012). A model of student workload. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 34(3), 239-258.

Impola, J. (2024). European credit transfer and accumulation system as a time-based predictor of student workload. Higher Education Research & Development, 44(2), 417–430.

Karjalainen, A., Alha, K., & Jutila, S. (2006). Give me time to think: Determining student workload in higher education. Oulu: Oulu University Press.

Kember, D. (2004). Interpreting student workload and the factors which shape students’ perceptions of their workload. Studies in Higher Education, 29(2), 165–184.

KU Leuven (z.d.). Hoe organiseer ik een studietijdmeting? Kwaliteitszorgportaal. Geraadpleegd op 30 juni 2025, van https://www.kuleuven.be/onderwijs/kwaliteitszorgportaal/onderwijskwaliteit/ ondersteuningsmateriaal/studietijdmetingen/hoe

Kyndt, E., Berghmans, I., Dochy, F., & Bulckens, L. (2014). Time is not enough. Workload in higher education: a student perspective. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(4), 684–698.

Marshall, S. (2018). Student time choices and success. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(6), 1216–1230.

Ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap (4 april 2003). Decreet betreffende de herstructurering van het hoger onderwijs in Vlaanderen. Brussel: Ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap.

Pogacnik, M., Juznic, P., Kosorok-Drobnic, M., Pogacnik, A., Cestnik, V., Kogovsek, J., ... & Fernandes, T. (2004). An attempt to estimate students’ workload. Journal of veterinary medical education, 31(3), 255-260.

Schrooten, H. & Vyt, A. (1999). Tijd voor studietijd: onderwijskundige, methodologische en beleidsmatige aspecten van studietijdmeting in het hoger onderwijs. Acco: Leuven.

Souto-Iglesias, A., & Baeza_Romero, M. (2018). A probabilistic approach to student workload: empirical distributions and ECTS. Higher Education, 76(6), 1007-1025.

Thornby, K., Brazeau, G., & Chen, A. (2023). Reducing student workload through curricular efficiency. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 87(8), 100015.

UAntwerpen (2021). Handboek kwaliteitszorg onderwijs. [Beleidsdocument] (toegankelijk voor UAntwerpen-personeel na inloggen)