Real social challenges require more than one view. In interdisciplinary education, students learn to connect perspectives and put forward integrated solutions together. In this teaching tip, you’ll see how as teacher, you can encourage that process in your own teaching.

We’ll discuss what interdisciplinary education actually is, what possible interpretations it can have, what competences are central to it and how to work on them.

What is interdisciplinary education?

Interdisciplinary education systematically combines knowledge, methods and perspectives from different disciplines to analyse and solve complex practical and social issues. It focuses on problems that don’t get solved from one discipline alone and therefore goes beyond subject-specific knowledge transfer: students learn to integrate perspectives, make critical judgements and collaborate across disciplinary boundaries (de Greef et al., 2017; Vienni-Baptista et al., 2024).

Take, for example, students from study programmes such as medicine, nursing, social work, pharmacy and occupational therapy learning working together in a team to solve a common problem, such as drawing up a care plan for a patient with multiple chronic conditions (see good practice 'interprofessional collaboration in healthcare (IPSIG)', only consultable for UAntwerp staff members, after logging in).

What possible interpretations can it have?

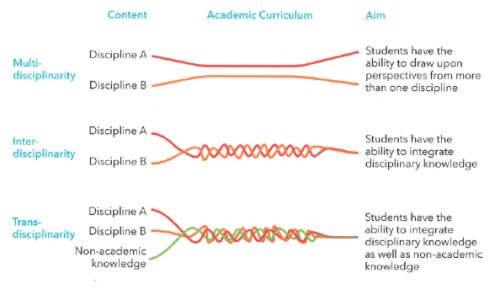

When reading about interdisciplinary education, there are inevitably the terms multi-, inter- and transdisciplinarity (de Greef et al., 2017). Often these terms are used interchangeably. We clarify here what’s meant by the different concepts, using the figure below.

Multidisciplinarity

We talk about multidisciplinarity when a particular topic, concept or theory is studied or approached from different perspectives. This logically leads to more knowledge and insight, but these remain separate. So there is no integration, nor new integrated insights or solutions. The focus here remains the study of the discipline itself, from a broader perspective. Consider, for example, a history study programme where students need to explain complex historical developments not only from their own understanding of history but also from theories and insights from behavioural and cultural sciences. Besides studying the student’s own discipline more broadly, multidisciplinarity can also serve as a stepping stone to interdisciplinarity.

Interdisciplinarity

In interdisciplinarity, insights from different disciplines are integrated to get a better/fuller understanding of a problem or question. So unlike multidisciplinarity, integration is a feature here. This integration leads to new, integrated knowledge and insights, while multidisciplinarity involves using already existing insights when studying one's own discipline.

Transdisciplinarity

Finally, transdisciplinarity adds another layer to interdisciplinarity. This also involves integration and new, integrated knowledge and insights. But this time, not only is the academic angle considered, but also the social one. The social field, experience-based experts and stakeholders are involved. As a result, the focus is on real-life problems, with all relevant factors and actors. Consider, for example, the sustainability challenges (wicked problems) within issues of sustainability (see also ECHO education tip 'think big, act small! The first steps towards sustainability education', 2022).

Which competences are central to interdisciplinary education?

Integrating insights from different disciplines first requires disciplinary knowledge. In doing so, students need not be experts, but understand core disciplinary concepts and methods so that they can discuss with each other in multidisciplinary groups (see also ECHO teaching tip 'how to classify students in group work', 2018, in Dutch).

In addition to disciplinary knowledge, there are competences for interdisciplinarity. Here, we distinguish two groups: competences aimed at initial exploration of interdisciplinary education and generic, transferable competences (de Greef et al, 2017).

1. Initial exploration

Competences aimed at initial exploration of interdisciplinary education (de Greef et al, 2017). For example:

- Knowledge and understanding of interdisciplinary education: what is it? What barriers and pitfalls exist? Which skills are important? What are the dos and dont's? What kind of cases are covered and how?

- Knowledge and understanding of the content of other disciplines, without working directly in an interdisciplinary way: multidisciplinarity as a step towards interdisciplinarity.

2. Generic, transferable competences

Generic, transferable competences (de Greef et al, 2017), aimed at learning to work in interdisciplinary contexts. Examples of these include collaboration, critical thinking, reflection and integrative reasoning. Here, students practise real interdisciplinary thinking and exchange.

Of course, initial exploration can be a stepping stone to more in-depth interdisciplinary (learning) work, but this can also be valuable at individual level. Small initiatives in interdisciplinary education certainly have their value (see also ECHO education tip 'starting with interdisciplinary higher education', 2019)!

How do you work towards interdisciplinary education?

Shaping interdisciplinary education depends on the competences you want to develop in students. If we focus on the initial exploration of interdisciplinary education, we think of teaching methods that focus more on applying knowledge and understanding. Think, for example, guest lectures, lectures, seminars and site visits. Looking at the generic competences, two central competences appear: cooperation and integration. After all, interdisciplinary education is all about students bringing together their knowledge from different disciplines.

A common teaching method here is the group assignment. To get the most out of such a method, consider the following aspects:

Make the group assignment group-worthy

Make the group assignment group-worthy (Lotan, 2003) (see also ECHO teaching tip 'what makes a group assignment successful' 2022):

- Choose open-ended, complex tasks that require higher levels of processing, making the 'group aspect' add value to the task. Strong(er) together!

- Encourage interdependence. Students need to integrate each other’s expertise to successfully complete the assignment, for example, when preparing integrated policy advice.

Support collaboration

Support collaboration during the group assignment and teach this:

- Collaboration is a competence in itself. Check to what extent your students have already mastered this. Recognise that learning to work together often requires more than just getting students to work together during a group assignment (see ECHO education tip, 2018).

- Collaboration goes better when it happens in a positive, pleasant atmosphere. Create a positive classroom climate (see ECHO education tip, 2020). Make it clear, for example, that making mistakes is normal, that constructive feedback is important and that students should help each other. Allow time to get to know each other, especially at the start of the group assignment (see, for example, good practice 'interdisciplinary project day' and 'Challenge-based learning during summer school social city design', only accessible for UAntwerp staff members, after logging in).

Keep in mind various prior knowledge

Students naturally bring diverse knowledge and experience to interdisciplinary teaching. Still, it can be useful to make sure everyone has the same basic knowledge. Are there certain theories, concepts or terms that are relevant to them all? Then be sure to provide that information at the start or prior to the group assignment (see, for example, good practice 'diamonds are forever', only accessible for UAntwerp staff, after logging in).

Besides group assignments, there are other teaching methods and learning activities that support interdisciplinary learning (Edelbroek et al., 2018). Always choose teaching methods with your educational goals in mind: what do you want students to learn and experience? For example:

- Promote a positive classroom atmosphere: use an icebreaker at the beginning of the group assignment.

- Encourage critical thinking: apply a pro and con grid apply.

- Broadening perspectives: get students to think outside their own field of study.

Want even more inspiration for teaching methods? The Library of facilitation techniques and the transition makers toolbox can help you for sure.

Want to know more?

ECHO Teaching Tips

- Think big, act small! De eerste stappen naar duurzaamheidseducatie (2022).

- Hoe studenten indelen bij groepswerk (2018)

- Starten met interdisciplinair hoger onderwijs (2019)

- Wat maakt een groepsopdracht succesvol (2022)

- Ondersteunen van samenwerkingscompetenties: Studenten 'leren' samenwerken (2018)

- Positive vibration yeah! Een positief klasklimaat (2020)

For UAntwerp staff members

Good practices:

- Interprofessioneel samenwerken in de gezondheidszorg (IPSIG)

- Interdisciplinaire projectdag

- Challenge based learning tijdens summer school social city design

- Diamonds are forever

Useful webpages

Relevant literature

About interdisciplinary education

- Boor, I., Gerritsen, D., de Greef, L. & Rodermans, J. (2021). Meaningful assessment in interdisciplinary education. a practical handbook for university teachers. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- de Greef, L., Post, G., Vink, C., & Wenting, L. (2017). Designing interdisciplinary education: a practical handbook for university teachers. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Edelbroek, H., Mijnders, M., & Post, G. (2018). Interdisciplinary learning activities. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Vienni-Baptista, B., Van Goch, M., Van Lambalgen, R., & Ellemose Lindvig, K. (2024). Interdisciplinary practices in higher education. Teaching, Learning and collaborating across borders. Routledge: Oxon.

About group assignments

- Burke, A. (2011). Group Work: How to Use Groups Effectively. The Journal of Effective Teaching, 11(2), 87-95.

- Lotan, R. (2003). Group-worthy tasks. Educational leadership, 60(6), 72-75.