- Open Access Policies and Experiences in Brazil: A Success Story? - Felipe César de Andrade

- Open Access at the University of Antwerp: a library point of view - Rudi Baccarne

- A student’s guide to Open Access - Joris Van Meenen

- From ‘Open Science’ to ‘Science’, lessons learned from this year’s Open Access week - Martijn Van Roie

Open Access Policies and Experiences in Brazil: A Success Story?

Felipe César de Andrade, Faculty of Law, Master of Laws, Student Researcher - Open Access Week 2020 – University of Antwerp

October 2020

The latest report from the Science-Metrix on the Open Access Availability of Scientific Publications (1) showed that up to 75% of the published articles in Brazil can be downloaded for free (2). It is the leading country in Open Access (OA) availability among those with large numbers of papers indexed by the Web of Science (WoS) (3). This report also points out that Brazil stands out in OA levels both for Gold as for Green Access (4).

This is the result of a 20-year ongoing process. As far as I am concerned, this process needs to be understood within the context of the constant struggle for scientific visibilty of countries that do not belong to the traditional north american-european axis of research (5). Having to deal with many financial and structural limitations, the Brazilian scientific community regards Open Access as one of the most feasible instruments to increase scientific visibility (6). It seems that the researchers did not take the wrong way, since it has been shown that articles available in Open Access receive 18% percent more citations on average (7).

It is hard to give an exhaustive overview of all factors that could explain this leadership from Brazil. In this text, I would like to explore three elements of particular relevance. First, I will discuss the role of the Scientific Electronic Library Online Brasil (SciELO Brasil) as a main promoter of Gold OA in Brazil (8). Second, I will describe the facilitator role played by the Creative Commons License (CC) in the expansion of Open Access. Then, I will show how public funding agencies and universities in Brazil haven been promoting Open Access for the scientific community. Finally, I will conclude with a note on potential further developments of the OA initiative and related challenges.

1. The Scientific Electronic Library Online: SciELO Brasil

The Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) was founded in 1997 and launched in 1998, with the support of the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) and the Latin-American and Caribbean Center of Information in Health Sciences (BIREME) (9). It is a repository and a bibliographic database, encomprising seventeen independent national collections accross Latin America, Iberian Europe and Africa (10). At present, the Brazilian collection consists of 296 journals (11).

Another important element of the digital library is the “SciELO Methodology”, a cooperative electronic publishing model of open access journals. This methodology is aimed at providing best practices in scientific journal management in a Gold OA model and at reducing interoperability costs (12). The implementation of this publishing model was very successful, and the journals belonging to SciELO are highly regarded by the international scientific community, in as much as the library has been indexed by Google Scholar, Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) and Scopus (13).

In its position as an institution of reference, the SciELO Publication Model has been used as a pathway for the implementation of public policies regarding the development of peer review journals (14). With that in mind, Gold OA was set as a default model rule in many policies, which helped to put away some misunderstandings and suspicions that surround the Open Access Initiative. This has certainly benefited the expansion of OA in Brazil.

2. Creative Commons (CC) License

The relationship between copyright and Open Access is not self evident. In Brazil, as in many countries in the world, copyright holders are entitled to exclusive economic and moral rights regarding their original works (15). OA is not against copyright, it enablers authors to use these rights in an “open” way in order to guarantee and enhance access to users and readers.

Scientific Journals and their readers may feel uncertain about the need to get an authorization from an author and may be unwilling to use them to their full extent out of fear about copyright violations. Therefore, the Creative Commons Licensing Model provides a useful tool to tackle this issue and to provide some legal certainty (16). It is a standardized public license, in which the reader can easily identify under which conditions the work can be used (17). Licensed use can range from allowing others to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the original work, even commercially, to allowing others only to download the original works and share them with others as long as the author is credited without possibility to modify the work in any way or use them commercially.

The CCs licenses are helpful for electronic journals, because they avoid legal uncertainty. Brazil was the third country to take part in this iniative, back in 2002 (18). This means that right from the beginning of massive internet use Brazilian electronic journals had a reliable legal structure at their disposal. Despite some incongruencies in journal’s editorial policies, mainly due to confusion about the legal terminology regarding copyright licenses, it is certain that Creative Commons were an important facilitator for the implementation of OA in Brazil.

3. Public Funding Agencies,Universities and Repositories

Despite the prevalence of OA publication in Brazil, there is no national policy that systematically coordinates the efforts in this direction. The initiative is dependent on individual initiatives from institutions, such as universities, public funding agencies and other scholarly initiatives (19).

Most public funding agencies require that their grantees publish their results in an accessible format. This can be done either by uploading pre-print versions in institutional repositories (Green OA) or by publishing in OA Journals (Gold OA). Most public funding agencies, however, do not seem to be financially structured to help researchers to publish in journals that have a high impact factor and charge high article processing charges (APC). Because OA Journals do not charge readers, some publishers have increased their APCs significantly in other to finance the transition to OA (20). The Federal Ministry of Education hosts an important journal subscription programme called Portal de Periódicos Capes, which is integrated nationally by the CAFE Platform (21). This programme, however, is subscription based, and does not deal with the problem of submission fees.

The Green OA infrastructure was initially put forward by the Brazilian Institute for Information in Science and Technology (IBICT), who tried to work together with universities and research centers and to provide proper training for the implementation of institutional repositories (22). IBICT has developed, for example, the Brazilian Open Access Portal on Scientific Information (OASIS.BR), which aggregates titles of Brazilian journals and Brazilian repositories. However, the adherence to Green OA in Brazil has not been nearly as successful as the one to Gold OA (23). Therefore, it would be important to gather information on local and thematic repositories accross the country and to propose a national policy that could enhance Green OA.

The lack of national AO coordination and specific policies leaves room for local and taylor-based initiatives by universities, such as the repository from the University of São Paulo (USP) and a portal of its own OA Journals – Portal de Revistas USP (24). The fragmentation between universities, however, limits the possibilities to leverage such projects to the level of international visibility.

Concluding remarks

In this text I tried to give an overview of the relevance of Open Access in Brazil and the main actors/institutions that are important for this policy. I first showed the protagonist role of SciELO Brasil; then I explained the facilitating role of Creative Commons Licenses by ensuring legal uncertainty. Lastly, I made some remarks on the fragmentary role played by public funding agencies and universities.

As for future developments in the field, we are currently moving from Open Access towards Open Science, including Open Data. This means that not only papers will be made freely available, but that research data sharing is evolving too. In this respect, it is essential to create sustainable publication models, and to build up the technology infrastructure that will enable a proper data management by different research partners. It would be interesting to see how far Brazil could go if the coordination between its many educational institutions would be strengthened. We have witnessed a success story with the availability of Open Access and SciELO, let’s hope that more similar initiatives will follow in the future.

References

(1) Science-Metrix Inc. Analyitical Support for Bibliometrics Indicators: Open Access availability of scientific publications. Montréal, Canada: January 2018.

(2) Science-Metrix. Analytical Support, 27.

(3) Science-Metrix. Analytical Support, 17.

(4) Science-Metrix. Analytical Support, 20.

(5) Abel Laerte Packer et al., “SciELO: uma metodologia para publicação eletrônica”. Ciência da Informação, Brasília, 27, no. 2 (1998), 111.

(6) Packer et al., “SciElO”, 111.

(7) Heather Piwowar et al., “The state of OA: a large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles”, Peer J, 6: e4375 (2018). doi: 10.7717/peerj.4375.(8) I follow the classification provided by Suber (2012, 6), who has a four-tier classification for Open Access. In the Gold OA, articles are make available directly by the publishers. In the Green OA, articles are made available by parties other than publishers, such as authors or repositories. Gratis OA, in its turn, refers to artucles without price barriers, whereas Libre OA refers to rticles without price barriers and without some permission barriers. Peter Suber, Open Access, (Cambridge: the MIT Press, 2012).

(9) Packer et al., “SciElO”, 111.

(10) Juan Pablo Alperin, “Open Access Indicators. Assessing Growth and use of Open Access resources from developing regions. The case of Latin America.” In Juan Pablo Alperin et al., Open Access Indicators and Scholarly Communications in Latin America. (Buenos Aires: UNESCO, 2014), 24.

(11) “SciELO Library Collection” , accessed 17 October 2020, https://www.scielo.br/?lng=pt.(12) Packer et al., “SciElO”, 113.

(13) Ariadne Chloe Mary Furnival et al, “As políticas de direitos autorais e reuso presentes nas revistas brasileiras de acesso aberto nas áreas biológicas e de saúde disponibilizadas na plataforma SciELO-Brasil", Encontros Bibli: revista eletrônica de biblioteconomia e ciência da informação, 20, no 44 (2015), 27, doi: 10.5007/1518-2924.2015v20n44p25.(14) Abel L. Packer. O modelo SciELO de publicação como política pública de acesso aberto [online]. SciELO em Perspectiva (2019) accessed 17 October 2020. https://blog.scielo.org/blog/2019/12/18/o-modelo-scielo-de-publicacao-como-politica-publica-de-acesso-aberto/,

(15) Federal Republic of Brazil, Copyright Law (1998), articles 7, 28, 29.

(16) Sérgio Branco. O que é Creative Commons? Novos Modelos de Direito Autoral em um mundo mais criativo (Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV, 2013), 20.

(17) “About CC licenses”, accessed 18 October 2020, https://creativecommons.org/about/cclicenses/.(18) Sérgio Branco, Walter Britto, O que é Creative Commons? Novos Modelos de Direito Autoral em um mundo mais criativo (Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV, 2013), 19.

(19) Marcelo Garcia, “Acesso Aberto: Fiocruz vem se consolidando como referência no tema no Brasil”, accessed 17 October 2020, https://portal.fiocruz.br/noticia/acesso-aberto-fiocruz-vem-se-consolidando-como-referencia-no-tema-no-brasil.

(20) Cleusa Pavan, Marcia Cristina Bernardes Barbosa, “Financiamento público no Brasil para a publicação de artigos em acesso aberto: alguns apontamentos”, Em Questão, vol. 23, no. 2 (2017), 121, 130.

(21) Portal de Periódicos Capes/MEC”, accessed 18 october 2020, https://www.periodicos.capes.gov.br/index.phpoption=com_pcontent&view=pcontent&alias=missao-objetivos&Itemid=109.(22) Sely M. S. Costa et al., “Acesso Aberto no Brasil: Aspectos históricos, ações institucionais e panorama atual”, In Eloy Rodrigues et al. (org.), Uma década de acesso aberto na Uminho e no mundo (Braga: Universidade do Minho, Serviço de Documentação, 2013), 134.

(23) Simone da Rocha Weitzel, “O mapeamento dos repositórios institucionais brasileiros: perfil e desafios”, Revista eletrônica de biblioteconomia e ciência da informação, 24, no 54 (2019).

(24) Patrícia Santos, Kátia Kishi, “Brasil é referência em acesso aberto, mas faltam políticas integradas”, accessed in 18 october 2020, https://www.comciencia.br/comciencia/handler.php section=8&edicao=111&id=1339.

Open Access at the University of Antwerp: a library point of view

Rudi Baccarne, Repository Manager - Anet Library Automation, - Open Access Week 2020 – University of Antwerp

October 2020

Open access has long been an important topic on the agenda of university libraries. Whereas in the early years (2000 and later) there was a rather modest resistance by librarians and scientists against rising subscription prices, today open access is a publication model with a significant market share.(1)

Scientific research results that used to be hidden behind the paywalls of scientific journals are becoming available free of charge to a wide audience.

FAIR enough

The University of Antwerp has always supported Open Access. The Berlin declaration on Open Access was signed by the then rector Prof. Francis van Loon in 2007. In 2014, a first open access policy was approved by the research council and the Board of Administration. The open access policy entails the obligation that all UAntwerp authors have to add the pdf of the final author version (the so called AAM – author accepted manuscript) or an open access publisher version when they register a peer reviewed journal article for inclusion in the academic bibliography.

The responsibility for the development of the infrastructure and administration has been entrusted to the university library. A logical choice. The many years of experience in rigorously describing, opening up and sharing scientific publications through library catalogues and academic bibliographies was the appropriate setting to build on.

The academic bibliography became an institutional repository by which bibliographic descriptions and linked full-text files can be accessed and shared. Making things Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR) is the new credo for Open Science, a credo that neatly matches with the library’s core business.

Share bibliographic data

The data from the institutional repository is shared with a variety of platforms and search engines. Examples are google scholar , OpenAire , ORCID, Unpaywall, but also databases and applications anchored in Flanders such as VABB-SHW and the Flemish research portal FRIS or UAntwerp applications such as the e-curriculum in PeopleSoft.

These integrations do not arise automatically, but are the result of well-considered technological choice and agreements that are in accordance with internationally accepted standards and protocols with regard to the storage, description and sharing of academic output .

Make publications accessible

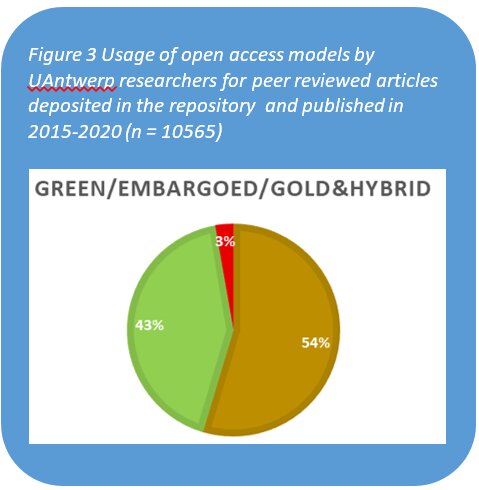

Today, the institutional repository archives 150,000 descriptions of scientific publications written by researchers from the University of Antwerp. The percentage of peer reviewed journal articles that are open access available via the repository increases annually. For articles published in 2019 more than 60% are freely available. Despite the open access policy, a significant number of peer-reviewed journal articles are still not in open access. These are articles subject to an embargo or of which we have not been able to reach (co) authors to request a suitable open access version.

Other publication types like datasets, books, book chapters, proceeding papers and others are open access available to a minor extent. This is mainly caused by two reasons.

First, the open access policy of the University of Antwerp mandates the deposit of an open access version for peer reviewed articles and only encourages the deposit of an open access version for all other types.

Secondly, the Belgian open access law that permits researchers to make their final accepted manuscript open access available is only applicable to peer reviewed journal articles.

Anet and Brocade

As of 1991, the university library has been held responsible for the production and maintenance of the academic bibliography for the University of Antwerp.

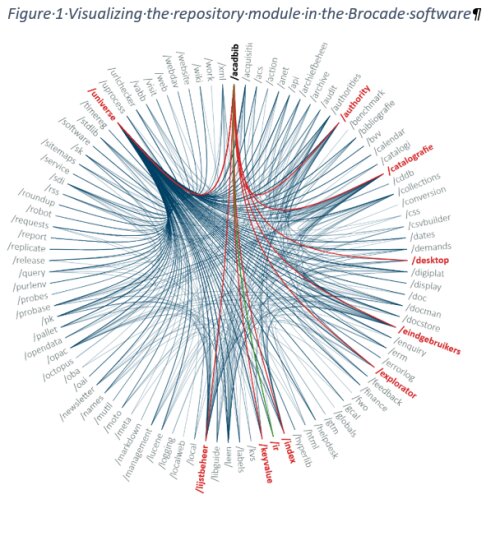

Over the years, the academic bibliography evolved from a merely bibliographic database towards a full text repository. Bibliographic data and according full text is stored with Brocade , in use since 2000 and developed by ANET, the University’s library automation team.

As shown in figure 1, the repository infrastructure is just a small module of the Brocade Library software. A module that takes full advantage of Brocade's storage and archiving functionality.

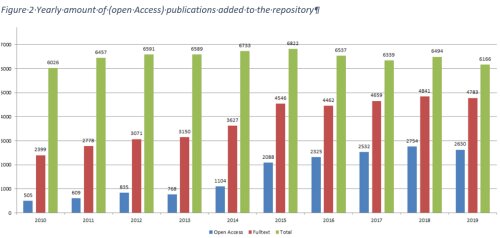

For all publication years and publication types that are covered by the institutional repository we have archived about 70.000 PDF documents in our database, good for 94 gigabyte disk capacity. 20500 documents are freely available. Figure 2 shows the annual growth of submissions of bibliographic descriptions and associated full text

Gold diggers and greenkeepers

Roughly speaking, researchers have the following options for publishing their articles open access:

- Publication in an open access journal. These are journals of which all articles are open access. The researcher usually pays a fee to publish the article. This is the gold model. The biggest advantage is that the publication is immediately available open access. A drawback is the cost price, with iincreases that are three times higher than inflation. (2)

Cost price at the moment is an average of 1500 dollars per article and peaks up to 6000 dollars per article.

- Publication in a subscription based journal where authors pay to remove the paywall for an article. This is called the hybrid model. Biggest advantage: immediate availability. Disadvantage: expensive and double dipping problem as institutions still pay for a subscription and researchers for publishing.

- Publication in a subscription based journal. The manuscript version is deposited in a repository. This author version or accepted manuscript will be made open access after an embargo period of 6 months (life sciences) or 12 months (social science & humanities). This is the green model. The big advantage is that it costs nothing. A drawback is that open access is only possible after an embargo period.

Tranformative agreements and new business models

Due to the increasing market share of open access and the rising cost of open access fees, universities and scientific publishers are looking for new agreements.

Where previously negotiations were mainly about the price of subscriptions and so-called big deals, multi-year bundled subscription packages to scholarly journals, there’s recently an evolution towards a new type of negotiation. With so-called transformative agreements different stakeholders try to achieve the transition from the traditional subscription model to an open access publication model. For the time being without success, witness the numerous examples of failed negotiations.

In the ideal scenario, a transformative agreement should result in universities paying publication fees instead of subscription fees. The big advantage of this model is that researchers don’t have to pay for open access in journals included in big deals, and that readers are no longer confronted with paywalls.. In this ideal scenario, all content is published according to the open access model.

In Flanders, university libraries are jointly, in consortium, negotiating with the publishers. When renegotiating, supporting and strengthening open access will always be included in our discussions with publishers.

Especially university libraries strive for a cost-neutral solution. Experiences with the read & publish models are not very promising and an extensive study by the European University Association shows that this is by far the most expensive approach.

Apart from the transformative agreements with the major publishers, there are other innovative models from smaller journals or research consortia that pursue a transparent pricing model. Some examples of initiatives supported by the University of Antwerp:

- Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis (Amsterdam University Press)

Uses a Subscribe-to-Open model, which uses existing revenues (subscriptions) to make journals completely free of charge.

- Open Library of humanities

Open Library of humanities is funded through a model of Library Partnership Subsidies to collectively fund the venue and its array of journals

- SCOAP 3

A global partnership of 3000 libraries, funders and research institutions

SCOAP3 has converted key journals in the field of High-Energy Physics to Open Access at no cost for authors. SCOAP3 centrally pays publishers for costs involved in providing Open Access, publishers in turn reduce subscription fees to all their customers, who can re-direct these funds to contribute to SCOAP3

Conclusion

There’s still a long way to travel in order to reach 100 % open access.

Apart from copyright restrictions and the high cost to publish in open access model, it is the evaluation model that slows down the breakthrough for open access. It is worth mentioning in this context that almost all respondents from a large-scale study by the European University Association find that the current evaluation model with an emphasis on impact factors and citations hinders the evolution towards open access. Authors and universities choose journals that advance their funding, careers and project applications, which are often hybrid journals from a major commercial publisher.(3)

But we will not be discouraged. Open access creates greater visibility for the research that is done at the University of Antwerp. Greater visibility means more usage and more usage means more societal impact. When it comes to usage, the repository’s log files on downloads speaks for itself. Traffic from robots and crawlers aside, 20,000 documents per month and more are downloaded from the repository since 2018.

Bibliography

1. van der Graaf M. Financial and administrative issues around article publication costs for Open Access [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Oct 22]. Available from: https://repository.jisc.ac.uk/6665/

2. Khoo S. Article Processing Charge Hyperinflation and Price Insensitivity: An Open Access Sequel to the Serials Crisis. Liber Q. 2019 May 9;29(1):1–18. Available from: http://www.liberquarterly.eu/articles/10.18352/lq.10280/

3. van Barneveld-Biesma A, Campbell C, Dujso E, Ligtvoet A, Scholten C, Velten L. Read & Publish contracts in the context of a dynamic scholarly publishing system [Internet]. Technopolis group; 2020 p. 91. Available from: https://www.eua.eu/resources/publications/932:read-publish-agreements.html

Open Access: A student’s perspective.

Joris Van Meenen, PhD student at the Antwerp Research Group for Ocular Science (ARGOS), - Open Access Week 2020 – University of Antwerp

October 2020

I’m Joris Van Meenen and I just started my PhD at the University of Antwerp so I’m quite the novice when it comes to scientific publishing and research dissemination, a fresh perspective if you will. Like many a scientist, I started my education being blissfully ignorant of the intricacies concerning research dissemination. I initially thought one would simply do the research and then share it with the world, but as it turns out, performing experiments is only half the work. After carefully analysing and interpreting the data, a manuscript has to be drafted which contains the rationale, methodology and results pertaining to the work. Additional effort should be made to write this manuscript as persuasive as possible because getting published in a reputable journal can be a journey in itself. While other methods of research dissemination do exist – more on that later – publishing in journals is currently the norm. However, being published in a journal is not synonymous with your article being globally available for all your peers to read and build upon. The European Open Science Monitor estimates that in the period of 2009 to 2018, over 60 percent of published articles were distributed in a pay-to-access format. Which begs the question. Why in the age of information is such a large amount of scientific information still locked behind a paywall?

Open the Blinders

The short answer is: money, for a longer answer I refer you to a wonderful documentary called ‘Paywall: The Business of Scholarship’. In brief, publishing companies have leveraged their historic position as distributors of paper-based journals to attain a certain form of prestige. Publishers can be thought of as ‘brands’ and each ‘brand’ has a certain form of prestige and impact associated with it. This is of utmost importance as employers/funding bodies will assess your impact level and look at the ‘brands’ you are associated with when shortlisting candidates. Such mentality has enabled publishers to garner a following that works for free, as it is prestigious to be allowed to review papers for certain publishers and it improves your odds of being hired/promoted. Even though most scientific journals have now cut the costs of printing paper by moving online and don’t pay a substantial part of their workforce, to access a single scientific article one is typically charged around 30 U.S. dollars. It is likely that publishers list individual articles at such prohibitively high prices to encourage subscription signups instead, where articles from various journals are bundled together at a lower cost per article. However, the Open Access movement does not agree with this status quo. Open Access advocates instead that since the majority of scientific research is funded with taxpayer money, the resulting output should be a public good and should not be locked away behind a paywall.

OA in a Colourful Nutshell

Now, how exactly does one publish Open Access (OA)? Is Open Access publishing even compatible with publishing in scientific journals? Well, Open Access is more of a general idea and it has a myriad of practical implementations so what follows can be considered a simplification. Open Access models encompass a spectrum of colours and metals, namely bronze, gold, hybrid, green, platinum and black, each with their own manner of providing articles free of charge. Bronze OA, also called Delayed OA, refers to journals that publish your work behind a paywall but then release the article publicly after a period of embargo. The term Gold OA is employed when the journal does not charge the reader through a paywall, but instead has the authors paying a fee for immediate and free availability of the article. However, these author fees can be as high as a few thousand U.S. dollars, which makes publishing in Gold OA journals not evident for younger research groups. Journals are regarded as Hybrid OA when they combine the standard paywalled publishing model with publishing Open Access through the aforementioned Gold OA model. Under the Green OA model, articles still have to be purchased by readers, but authors are allowed to share a version of their manuscript in a repository. This is actually your right as an author according to Belgian legislation (Art. 29): after a maximum embargo period of 12 months for Social Sciences and 6 months for any other field of science, Belgian authors have the right to deposit the latest version of their manuscript in a publicly available repository if the corresponding research was funded for the majority by public funding. The pinnacle of Open Access seems to me the Platinum OA model as neither the readers nor the authors are charged any payment for providing scientific articles. Platinum OA journals rely instead on the generosity of donors but can also employ intrusive advertisements to cover costs, which diminishes the reading experience. Finally, there is ‘Black OA’, which is technically not an Open Access model for publishing but rather an umbrella term for ways to access content that is otherwise locked behind a paywall. This includes illegal sharing sites or the hashtag #ICanHazPDF on Twitter.

To accelerate the transition towards a future of Open Science, a group of 11 research funders backed by the European Commission and the European Research Council (ERC) formed a coalition on 4 September 2018, cOAlition S. Their plan, Plan S, is simple: from 2021 onwards, all scientific publications that result from research funded by members of cOAlition S must be published in compliant Open Access journals or platforms. Currently at 25 members, the coalition’s impact on the state of scientific publishing will steadily increase as they gather more and more members. However, Plan S has been met with great resistance from various publishers and with the ERC Scientific Council recently withdrawing its support, it remains to be seen whether Plan S will indeed be implemented.

Consider Other Audiences

For me, the Open Access movement could broaden its scope to include some additional lines of thought. Whereas the current focus lies on making scientific articles freely accessible for human readers, it would be prudent to also think about the future. Each day, over 2000 citations are added to PubMed and the ever-increasing body of scientific literature has reached a point where keeping up with general topics has become a tremendous task. As a result, search engines are routinely employed to sift through the constant stream of information in order to locate articles relevant to one’s field of study. However, the caveat of this method is that your search results might omit some interesting papers due to them not matching your search terms and by only focussing on your specific field of study, you might lose track of the bigger picture. In order to be Open towards the future, scientists should start thinking about a publishing format that facilitates computer-based high content analysis, for example, by including a machine-readable section in the abstract that summarises the results in a standardised manner.

Another audience that is becoming increasingly important to reach are the non-scientists. Disputes about vaccines and climate change show that the gap between scientists and non-scientists – even between scientists of different fields – is widening due to the increasing complexity of research. Bridging this gap through other means of research dissemination such as podcasts, news articles and events like Pint of Science can help prevent scientists from losing the public trust. Now, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s more important than ever that healthcare professionals, policy makers, funders, patients, students & educators, and the general public have access to accurate scientific information.

There is still much work to be done before all scientific publications that arise from tax payer funded research are made freely and immediately available. Open Access will not only enable greater collaboration and data access in research, but it will also benefit society as a whole. I hope that my article has given you some food for thought and increased your understanding of the Open Access movement.

Bio

Joris Van Meenen is a first-year PhD student at the Antwerp Research Group for Ocular Science (ARGOS). During his undergraduate studies in Biochemistry at the University of Antwerp, Joris already showed an interest in translational science by working together with students from KU Leuven to develop a biosensor for fast and accurate quantification of Vancomycin – which won gold at the SensUs student competition. Now, at ARGOS, Joris is learning the principles of tissue engineering to develop an organ-on-a-chip device that mimics the human cornea. When implemented, this device will facilitate better preclinical testing of ophthalmic drugs, reducing the amount of costly clinical trials with candidate compounds that are toxic or ineffective.

From ‘Open Science’ to ‘Science’, lessons learned from this year’s Open Access week.

Martijn Van Roie, Expert e-sources and Open Science at the UAntwerp library, Open Access Week 2020 – University of Antwerp.

October 2020

“The critical importance of open and free exchange of scientific information cannot be underestimated and is an essential aspect of a modern and future-oriented society.” With these strong words opened Vice-rector Research Professor Ronny Blust this year’s Open Access week at the University of Antwerp. Over the recent years, a strong advocacy for so-called ‘Open Science’ has been growing strongly in the research community, pleading that science should be publicly available, be reusable, induce collaboration and be transparent. This Open Science is not as straightforward as one might think, where in present science, the open and closed system are living in an elbowing harmony. Indeed, the importance of having the scoop as a researcher often contrasts the open sharing of information for global efficiency, and on top of that, scientific publishers are wielding high publication and/or reading fees for monetary gain. This persistence of a closed system is only minutely the researchers’ fault, since we are still depending on a funding and publishing system that started in medieval times[1]. However, developments in the last decade have made it clear that the tide is turning. As Mick Watson asked for in his famous 2015 paper, “When will ‘Open Science’ become simply ‘Science’?”[2], there is a tangible drive within the scientific community to rid itself of the burden of a faulted system. We are rethinking how to publish, how to evaluate scientific impact, how to collaborate and how to enhance reproducibility and integrity.

This year’s Open Access week made it clear that there is a strong will in our University to take the extra step, not only from the researchers, but also from the research staff and administration. The different talks, blog posts and video testimonials touched many aspects of Open Science. Together with the Belgian Open Access week webinars, which were more focused on research administration, we were handed a nice and handy set of tips and tools. Nevertheless, why should we care about Open Science? Moreover, what are the pitfalls we yet need to overcome?

Understanding the why

Professor Colebunders, a big advocate of Open Access publishing, stated in his testimony that rapid and open availability of research results in the scientific community is crucial. However, why is Open Science so important? Truth being, one can argue that keeping research data closed also has its advantages. As our colleague Dr. Bronwen Martin from the faculty of pharma, biomedicine and veterinary sciences explained in her talk during the Belgian program, Open Science can accelerate science when thought trough carefully. This question, the why of Open Science, was also the main theme of the video testimonials of our researchers, and support the general consensus on the benefits on open research in the research community (Fig. 1). Dr. Bert van den Bogerd, postdoctoral researcher at the UA, explained how open research publications and data can lead to more visibility for a researchers work, enhancing (inter)national collaboration and increasing visibility for the non-academic world. The latter view was strongly endorsed by Anthony Liekens, alumnus and citizen scientist, who gave an example about using research results to correctly develop mouth masks in the current Covid pandemic. Citizens and non-academic experts like practitioners usually can’t afford articles behind a steep paywall, and greatly benefit from freely available research. Open Science thus does not only enhance a researcher’s visibility, but strongly enhances societal impact. Hanne Leysen, PhD student at the UA, thus pleaded for more outreach events to communicate with the general public. Lastly, as stated by professor Maudsley and PhD students Matthias Govaerts and Marlies Boeren, Open Data and publications allow for development of a broader understanding than that which can be achieved by one research project alone. Endorsed by the blog post of Joris van Meenen, if we even can expand our search for answers by supplying machine-readable open formats, we are well on our way to answer big questions about the world. To finish, during an interesting talk about open research data and research integrity, professor Sabine Van Doorslaer (UA) explained how open data can lead to a lower degree of research fraud. This by providing means for quality assurance and by improving reproducibility of the research[3].

Figure 1: Different ways of how Open Access can improve the overall research process. Both reasons for personal benefit (e.g. more exposure and higher citation rates) as well as societal benefit (e.g. better access for researchers in developing countries and practitioners) are generally agreed upon in the research community. Picture by Danny Kingsler and Sarah Brown, CC-BY.

Strengthening the foundations of Open Science

Although the importance of Open Science is nowadays broadly understood and supported by the research community, researchers are still bound to evaluation systems and publishers agreements that slow down transitions to Open Science systems. Luckily, legislators are slowly recognizing the importance of Open Science as well. Recent advances led to the formation of the European Open Science Cloud, the Flemish Open Science Board and many others, endorsing the need for Open Science. A big milestone was the adoption of the Belgian Open Access provision in 2018, which allows researchers to overrule most restrictions of publishers and to make the author accepted manuscript (AAM) of their research papers open access through an institutional repository (so-called ‘Green’ open access). This law, together with our own institutional open access policy, allows for a broad dissemination of research results. As stated by Rudi Baccarne in his blog article, behind this process stands a diligent research administration that manages the institutional repository, advises researchers in all aspects of Open Science and looks for new ways of enhancing this, e.g. by exploring the possibilities for ‘transformative agreements’ and cooperative electronic publishing models (see the blog article of Felipe César de Andrade for examples from Brazil)

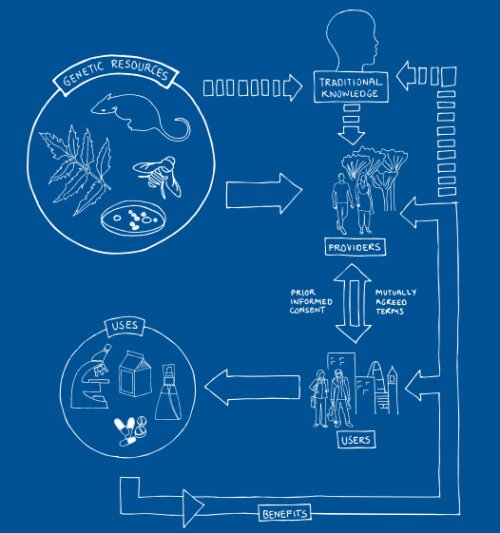

Nonetheless, since science is a quickly evolving field and legislation tends to be rather static, it is often challenging to keep laws up to date and future-proof. A pertinent example of this was given in the lecture of Professor Esther van Zimmeren (UA) about the Nagoya protocol on the sharing of benefits from genetic resources (Fig. 2). Prof. van Zimmeren’s talk did not only clearly show the need for fair and equitable sharing of benefits of research data and resources, but also showed some pitfalls in which legislation still needs to grow in order to make this happen. As an example, she showed that the ever-growing dissemination of digital sequence information (DSI) leads to pressing concerns about how to provide legal certainty. Luckily, this field is also evolving, with the WILDSI report[4] as a great example of the work that has been going on to provide a sound legal framework for Open Science.

Figure 2: The rationale of the Nagoya protocol on access and benefit sharing. Provider countries hold legal ownership on their natural genetic resources and their traditional knowledge. When users like researchers and companies want to make use of these resources, it is expected and regulated by the Nagoya protocol that the benefits of this use is shared fair and equitable with the provider country. Of course, when pleading for open data, legislation has to find a way to deal with digital sequence information to defend this sharing of benefits. Picture from Copyright (2011), Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Next to the possibility to make research publications and data openly accessible, of late, funding bodies have been making it increasingly more obligated to do so. A big part in this story is the need for transparency in how research data is being handled, made openly available and stored for later reuse. This need for FAIR data (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable) and the obligation for a transparent Data Management Plan (DMP) was clearly explained during the talk of Dr. Jord Hanus, Head of the Research Affairs Office of our University, and many other talks during the Belgian Open Access week program. Filling in a DMP transcends just being an administrative burden. It is a way to ensure a correct handling of the data and can be indispensable in collaborative (inter)national projects. Fortunately, help is always available through the research administration. Lastly, funding bodies are taking matters in their own hands to provide means of Open Access publishing. A talk by Michael Markie in the Belgian program showed the new plans for a European publishing platform, ORE (Open Research Europe). This platform, designed for Horizon2020 grantees, will provide an open and transparent review process and publication, ensuring compliance with Europe’s Open Science goals, and importantly, being absolutely free of charge. Together with ORE, recent initiatives like F1000 and Peer Community In’s (PCI’s) are rethinking the way we validate, share and publish our research results.

Drowning in tools

What has been particularly apparent during this week’s talks, especially from the Belgian Open Access week, is that there is a sheer amount of tools to help researchers and especially administrators to advance their institute’s Open Science agenda. Countless tools like Unsub, Unpaywall, Sherpa Romeo, Zotero, Zenodo, ORCID, draw.io, GitLab, Atom, etc. exist (Fig. 3). Furthermore, there is an increasing prevalence of educational material about Open Science (and even ‘training the trainer’ material) scattered around the web. In this strength also lays its weakness, since the amount and diversity of tools leads to it that one may not see the wood for the trees. It is in the current era of digital information quite easy to drown in the never-ending supply of supporting material. In that respect, it is extremely important to keep in mind that these tools are not a goal in itself, but should be selected and used only if clearly helpful for advancing Open Science.

Fortunately, universities and other institutes can increasingly depend on administrators like librarians and repository managers to guide them through the landscape of Open Science. Some recent developments in providing guidance and support look very promising. For example, Paula Oset Garcia from the UGent presented during the Belgian webinars the new EOSC Pillar platform, providing a database on all of the abovementioned tools and resources. Other initiatives like the OpenAIRE Provide platform aim to link different repositories and their metadata together. This way, at least we will be able to maintain an overview and find the common thread in the Open Science landscape.

Figure 3: Non exhaustive representations of the sheer amount of tools that exist for every part in the research process. The green line is just one of the many possible combinations of these tools, and it is getting more and more important to provide sufficient guidance for researchers in this landscape of tools. Picture: Joint Roadmap for Open Science Tools (JROST).

Little by little, one walks far

To summarize, this year’s Open Access week provided valuable insights, tips and tools to further enhance the Open Science agenda of our University and our researchers. Open Science offers valuable advantages, a viewpoint increasingly shared by scientists worldwide. Not only does open access publication of research data and papers provide more visibility and options for collaboration for the researcher; it can greatly enhance societal impact, provide citizens and non-academic experts with up to date information and allow overarching research to answer big questions about the world and our universe.

Legislation is slowly but steadily acknowledging the need for a more open and transparent research process, and is step by step providing us with the tools to back this up. Although some legislative challenges still remain, the shift in view is noticeable and funding bodies are backing this up with new regulations and platforms for researchers to take the step. Furthermore, the research community can count on a strong research administration to guide them through these regulations and the sheer amount of tools and information increasingly available on the web.

The saying goes ‘little by little, one walks far’. Let’s not stop here. Some very fundamental problems in the way we evaluate and fund research, together with a faulty and wildly expensive publishing system still remain. But as a research community, where solving problems is our job and falling and getting up is just an occupational hazard, I’m sure we will find a solution. That’s what scientists do.

Special thanks

Organizing weeks like these take a lot more than you would think, so I would like to warmly thank the organizing committee of the Open Access week at the University of Antwerp: Bronwen Martin (UA), Rudi Baccarne (UA), Esther van Zimmeren (UA), Marianne De Voecht (UA). I would also like to thank the numerous people who organised the Belgian Open Access week, of which I don't know everyone by name. Thank you all! Lastly, a special additional thanks to Bronwen Martin, without whom the testimonials would not have been possible.

References

1. David, P. A. (2008) "The Historical Origins of 'Open Science': An Essay on Patronage, Reputation and Common Agency Contracting in the Scientific Revolution, Capitalism and Society 3:2, Article 5. doi:10.2202/1932-0213.1040

2. Watson, M. (2015) When will ‘open science’ become simply ‘science’?. Genome Biology 16, 101. doi:10.1186/s13059-015-0669-2

3 . Baker, M. (2016), 1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility. Survey sheds light on the ‘crisis’ rocking research. Nature 533, 452–454, doi:10.1038/533452a

4. Scholz, A.H., Upneet,H., Freitag,J., Cancio, I., dos S. Ribeiro, C., Haringhuizen, G., Oldham, P., Saxena, D., Seitz, C., Thiele, T., van Zimmeren, E. (2020) WILDSI, Finding compromise on ABS & DSI in the CBD: Requirements & Policy ideas from a scientific perspective. Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, BMBF. 49pp.